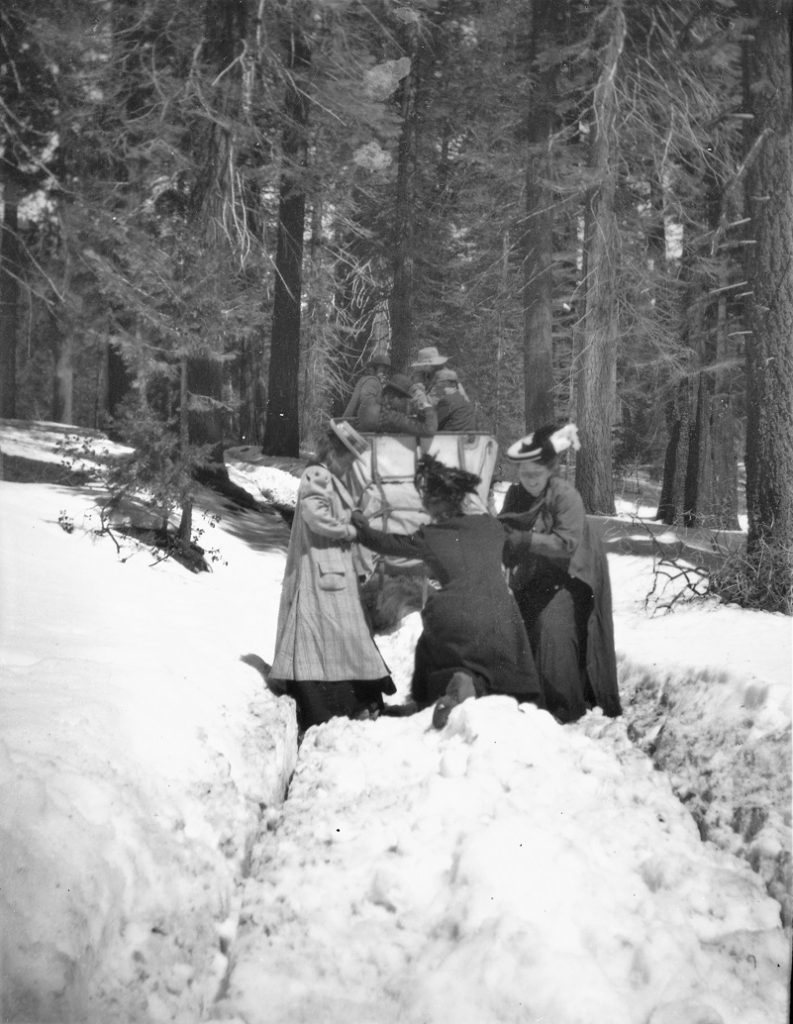

Historic photographs help paint the picture of what it must have been like to ride a stagecoach up this old road back in the day. Not having a stagecoach available I did the next best thing, walking up that dirt road though the snow, ice and mud.

Distance: About 6 Miles (but you can go shorter or longer)

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Range: 3,401′ to 4,798′

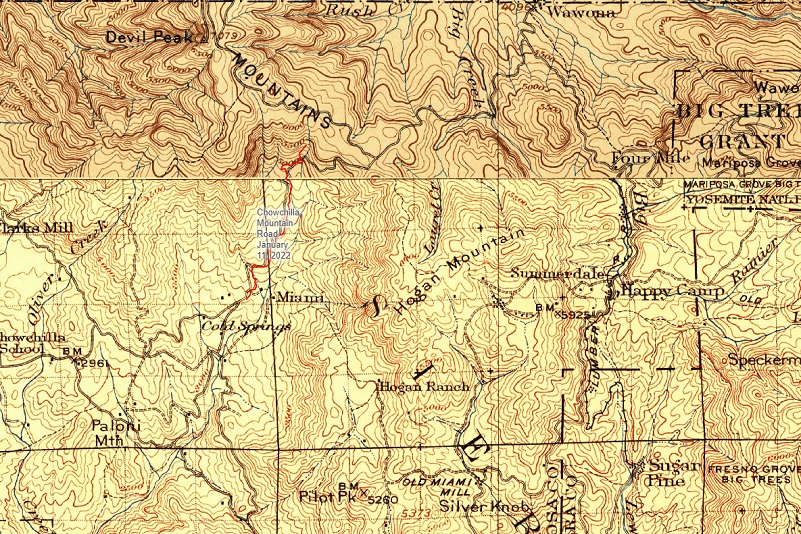

Date: January 11, 2022

CALTOPO: Harris Cutoff Up Chowchilla Mountain Road

Dog Hike: Maybe

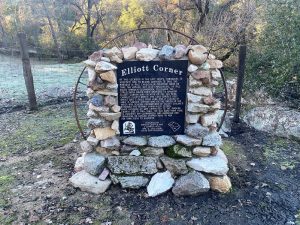

Trying to follow the route of the old 14 mile stagecoach journey up Chowchilla Mountain Road, I decided to walk it in chunks. I had previously hiked the section of the road up to and slightly beyond where the Cold Springs Stage Stop was located. It was a good day to walk that old wagon road out some more. But first, I made a quick stop shortly after I turned off of Hwy 49 onto Chowchilla Mountain Road at the E. Clampus Vitus Monument for Elliott Corner erected April 6, 2013 by the Matuca Chapter. The Monument read:

Trying to follow the route of the old 14 mile stagecoach journey up Chowchilla Mountain Road, I decided to walk it in chunks. I had previously hiked the section of the road up to and slightly beyond where the Cold Springs Stage Stop was located. It was a good day to walk that old wagon road out some more. But first, I made a quick stop shortly after I turned off of Hwy 49 onto Chowchilla Mountain Road at the E. Clampus Vitus Monument for Elliott Corner erected April 6, 2013 by the Matuca Chapter. The Monument read:

At this location in the late 1800’s, travelers to Yosemite had to decide whether to take the arduous 14 mile Chowchilla Mountain Road or take the longer, or less challenging, 24 route through Cedarbrook, following the stageroute from Raymond to Wawona. Elliot Corner was located on the 320 acre Charles Elliot Ranch. The Cold Springs Post Office was 3 miles from here and it closed in 1883. A service station was on the ranch in the 1920’s and several generations of Elliot children attended the nearby Chowchilla School. When Highway 40 was completed to the Madera County line in May 1969, the old road from here to Yosemite via Cedarbrook was bypassed and travelers no longer stopped here to ask for directions to Yosemite.

My December 20, 2020 Blog has more information about Elliott Corner, along with Charles “Charlie” Monroe Elliott and his wife Ida May. This time I drove up the road a bit farther to walk up Chowchilla Mountain Road along part of what was a historic wagon road. I drove up a little past the intersection of Chowchilla Mountain Road and Harris Cutoff to where the pavement ended then I starting walking up the dirt road in the long ago tracks of old wagons, stagecoaches and travelers back in the day.

To begin with, here is some history on the various routes to Wawona from Wawona’s Yesterdays by Shirley Sargent:

In 1869, Galen Clark organized a stock company of eight men to build a wagon and stage road from Mariposa as far as Clark’s (Wawona) which was used as a toll road from 1870 until 1917.

The “Mariposa Big Trees and Yo Semite Turnpike company” reorganized again in 1870; it now had the backing of some additional Mariposa County investors. John Wilcox, a Mariposa businessman was president; Moore was secretary, and Clark treasurer.10

A survey of the planned road by Jarvis Kiel was quickly completed and by the summer of 1870 the “Chowchilla Mountain Road” was open from Mariposa via White & Hatch’s Ranch to Clark & Moore’s on the South Fork. The road cost $12,000, half being put up by Clark and $2,000 by Edwin Moore, with the balance from a mortgage on their holdings. On 10 June 1870, the Mariposa County Board of Supervisors authorized the builders to collect tolls from travelers. The first stagecoaches, owned by Henry Washburn of Mariposa and two partners, began carrying passengers over the road to reach what is now Wawona.

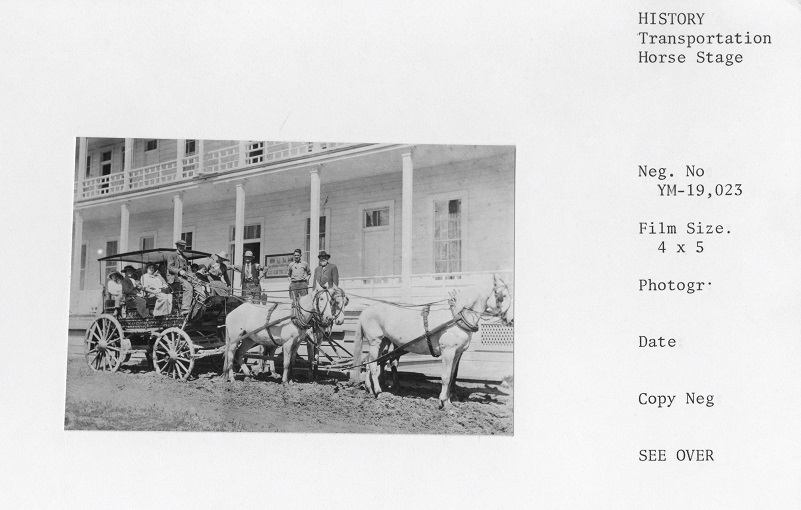

Yosemite National Park has a wonderful resource of historic Public Domain photographs on their Digital Archives Home Page and I located a couple of pictures of the Washburns and their stages at the Wawona Hotel.

Stage coach “Yosemite” at the Wawona Hotel. Al Stevens – Driver; John Washburn – man standing with beard; and Clarence Washburn (?). (Yosemite Digital Archives)

Although Clark was a commissioner and the first Guardian of the Yosemite Grant, he apparently had a great difficulty in securing his promised salary. This shortcoming, coupled with his ambitious building and promotion projects, forced him into a series of additional mortgages. By this point, only the extension of the road from his development on the South Fork on to the Yosemite Valley seemed likely to put him out of debt. However, completion of the Chowchilla Mountain Road renewed hopes for drawing in more Yosemite tourists, and in May 1870 Clark and Moore opened “Clark’s Station,” a rustic lodging that was the predecessor of the Wawona Hotel. Clark depended on Moore and Moore’s capable wife, Huldah, to operate the inn while he was involved in road promotion and construction.

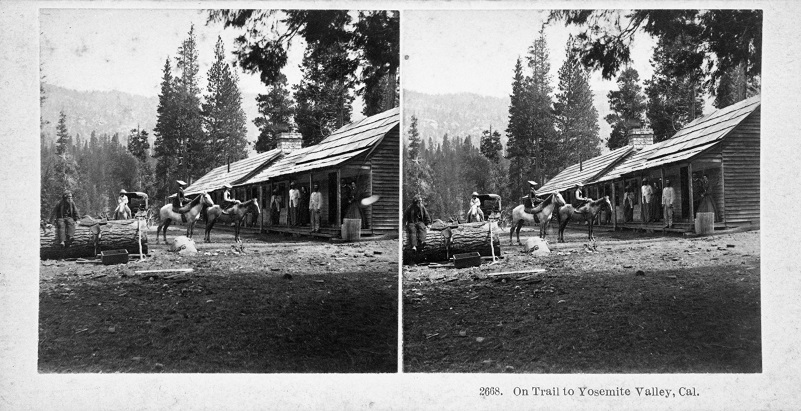

Captioned: “2668. On Trail to Yosemite Valley, Cal.” Clark’s Station. (From Yosemite Digital Archives, From L. Smaus Collection)

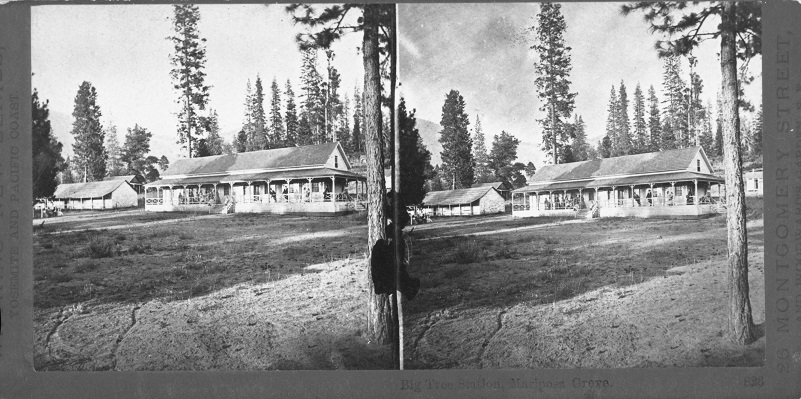

“Big Tree Station, Mariposa Grove, 826” Clark’s Station. (From Yosemite Digital Archives, From L. Smaus Collection)

As early as 1870, Clark had a survey made for a wagon road from his lodging at Wawona to Yosemite Valley. This road was begun by Chinese laborers, under the direction of John Conway and Edwin Moore and finished by Washburn, Chapman & Company in July, 1875.

Most of the 16-foot-wide road was constructed during severe winter weather. The era of the stagecoach, which was to continue, in jolting, dusty fashion for forty years, began for Yosemite-bound visitors

By mid-April, 1875, the rough road was passable for stagecoaches except for a narrow, 300-yard section still under construction near the old Inspiration Point. To the passengers’ temporary inconvenience and amusement, they walked the unfinished stretch while their quickly-dismantled stage was carried in pieces by hand, then reassembled, harnessed up, reboarded and driven off with considerable aplomb.

The Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Company (Washburn brothers), ran stages from Merced to Wawona via Mariposa where they had a livery stable.

The road from Raymond to Wawona generally followed the route of present State Highway 41, while the stage route from Mariposa, called the Chowchilla Mountain Road, exists today, rutty, dusty and little-changed from its 1870 route.

The Wawona Hotel was a logical and popular overnight stop for stage travelers, and the Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Company, operating two stage schedules and 700 horses, saw to it that their passengers traveled speedily and safely, though dustily.

In 1865, 369 hardy, saddle-sore travelers visited Yosemite. In 1875, mostly in stagecoaches, the Park had 2,423 visitors; 2,590 in 1885; 8,023 in 1902; and in 1914, when automobiles were allowed on the Wawona Road, 15,154. Travel doubled in 1915 when 31,546 visitors chugged in; 209,166 came in 1925 and 498,289 in 1932, the last year of Washburn ownership.

To help put those numbers in perspective, the park shows the following number of recent visitors with the year in parenthesis: 2,360,812 (2020), 4,586,463 (2019), 4,161,087 (2018), 4,479,242 (2017), 5,217,114 (2016), 4,294,381 (2015), 4,029,416 (2014), 3,829,361 (2013).

The Wawona Road accounted for a number of Yosemite “firsts.” The first automobile to enter the Valley traveled it in 1900, and 32 miles of it had the honor of being the first paved road in the Yosemite region in June, 1902 Mud and dust were tamed! Here is a link to an expired action with an image of a 1900 brochure for the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company.

Soon increased automobile traffic made oiled roads a necessity and, in 1932, the new, modern Wawona Road was completed from the South (Fresno) Entrance to Yosemite Valley.

After 1932, one South Entrance Station replaced the three stops maintained by the Turnpike Company. Tolls had been abolished in 1917, but traffic in and out of the Park from the Washburn domain had been checked until it became part of the Park.

There are many wonderful sources for what the travel on these old roads was like. One of those sources is One Hundred Years in Yosemite by Carl P. Russell where he shares the following:

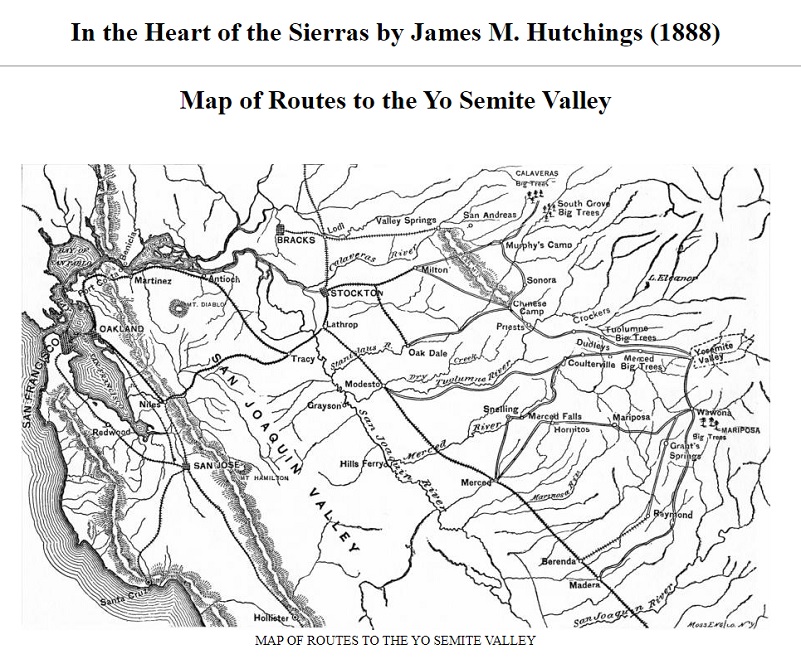

In keeping with this wagon-road building was the steady extension of the Central Pacific Railroad. Stockton, Modesto, Copperopolis, Berenda, Merced, and Madera were, in turn, the terminals. Seven routes to Yosemite made bids for the tourist travel. The Milton and Calaveras route permitted of railroad conveyance to Milton. Those who were induced to take the Berenda-Grants Springs route took the train to Raymond. The Madera-Fresno Flats route afforded railroad-coach transportation to Madera. The Modesto-Coulterville route meant leaving the rails at Modesto. The Merced-Coulterville route involved staging from Merced. The Mariposa route also required detraining at Merced, but the stage route followed took travelers through Hornitos and Mariposa. Those tourists who chose the Milton-Big Oak Flat route left the train at Copperopolis and traveled in the stage to Chinese Camp, Priests, and into the valley on the Big Oak Flat Road. Dodgers, pamphlets, and guidebooks furnished by the competing towns and stage companies produced a confusion to say the least.

The conveyances were of two types. At the height of the season, when travel was heavy and roads dry, the Standard Concord Coach was employed. At other times, a vehicle commonly termed a “mud wagon” was put to use. During this era of horse-drawn vehicles, the trains of pack mules were, of course, replaced by great freight wagons. Today, in driving over the old wagon roads, one is led to wonder how passenger vehicles succeeded in passing the great freight outfits. Some years ago, in searching through the objects left in a deserted house in the ghost town, Bodie, I came upon a manuscript describing staging as it was practiced in that famous mining camp. What the unknown author has to say about the business there applies to neighboring mountain regions, and is a reminder of a phase of life of the ’eighties.

The stage coach is to California what the modern express train is to Indiana, and people unaccustomed to mountain life can form but little conception of the vast amount of transportation carried on by means of coaches and freight wagons.

Even though California may truly be termed the “Eden” of America, yet there is not a county in the state but has more or less traffic for the stage coach, and in the northern and eastern part of the state, especially, there is an entire network of well-graded roads, resembling Eastern pikes. These roads are mostly owned by corporations and, consequently, are toll roads.

Over these are run the fast stages drawn by from two to ten large horses, and the great freight wagons drawn by from fourteen to twenty mules.

The stage lines have divisions, as do railroads, and at the end of each division there is a change of horses, thus giving the greatest possible means for quick conveyance. Over each line there are generally two stages per day, one each way. These carry passengers, mail, and all express traffic. At each town is a Wells Fargo office, and business is carried on in a similar manner to that of railroad express offices. Telegraph lines are in use along the most important roads.

The stage lines have time cards similar to railroads, and in case a stage is a few minutes late, it causes as much anxiety as does the delay of an O. & M. express. A crowd is always waiting at the express office; some are there for business, others through some curiosity and to size up the passengers.

A stage from a mining town usually contains a bar of gold bullion worth $25,000, which is being shipped to the mint. Bullion is shipped from each mine once a month, but people always know when this precious metal is aboard by the appearance of a fat, burly officer perched beside the stage-driver, with two or three double-barreled shotguns. He, of course, is serving as a kind of scarecrow to the would-be stage robbers.

The average fare for riding on a stage is 15 cents per mile.

The manner in which freight is transported is quite odd, especially to a “Hoosier.” Wagons of the largest size are used. Some of these measure twelve feet from the ground to the top of the wagon bed; then bows and canvas are placed over this, making a total height of fifteen feet, at least. Usually three or four of these wagons are coupled together, like so many cars, and then drawn by from fourteen to twenty large mules. All these are handled by a single driver. A team of this kind travels, when heavily loaded, about fifteen miles per day, the same being spoken of always as the slow freight. In some mining districts, however, where business is flush, extra stages are put on for freight alone. These are termed the fast freights. This business involves a large capital, and persons engaged in it are known as forwarding companies. Even the freight or express on goods from New York is sometimes collected a hundred miles from any railroad, and so even to those living in the remote mountain regions, this is about as convenient, and they seem to enjoy life as well as if living in a railroad town.

The road steadily gained elevation and I imagined how those stock pulling the coaches and wagons certainly had their work cut out for them to pull that grade toward Wawona. It wasn’t long before the shady spots of the road started holding more snow. I had hoped that snow, ice and mud wouldn’t be much of an issue but I wouldn’t really be sure until I tried it.

But how did those wagons and stagecoaches back in the day deal with heavier snow and ice on this road?

Well, here is apparently one way.

The road started getting a little muddier and I decided it was time for me to turn around. Slipping and sliding in the mud just didn’t sound like fun to me.

Heading back down the road gave me a nice view of the north side of Pilot Peak and the Silverknob area that I often wander around.

There are many roads and trails to explore in this area and many don’t show up on Topographic Maps. CALTOPO or using a download to the Avenza Map APP are the best that I have found. Links are below the Maps and Profile section toward the end. Once I started walking, a couple of pickups came down the road, but I didn’t see anyone on this hike. A big reason is that this road is not maintained during the winter so the road conditions are not conducive to most vehicles. During the summer, that is a different story though. These roads do get use from motorcycles, 4 wheelers, bikes, horses and hikers. I suggest you be prepared because the motorcycles can fly by in an instant but you can hear them coming. I try and avoid the weekends in this area for that reason.

Dog Hike? Maybe

This could be a good dog hike if your dog is a good fit. The road is lightly traveled by vehicles so you would need to keep an eye open for a vehicle coming around one of the curves. In the summer you could run into a rattlesnake out here also. This is mountain lion country, along with other wildlife that you could encounter. There were a couple of areas with running water on my hike but it can dry up in summer, so you would probably need to pack dog water.

Doarama:

What is a Doarama? It is a video playback of the GPS track overlaid on a 3 dimensional interactive map. If you “grab” the map, you can tilt it or spin it and look at it from different viewing angles. With the rabbit and turtle buttons, you can also speed it up, slow it down or pause it. The track used to create this week’s Doarama is a one way track, going up the road.

Cold Springs up Chowchilla Mountain Road

Maps and Profile:

CALTOPO has some free options for mapping and here is a link to my hike this week, which you can view or download: CALTOPO: Harris Cutoff Up Chowchilla Mountain Road

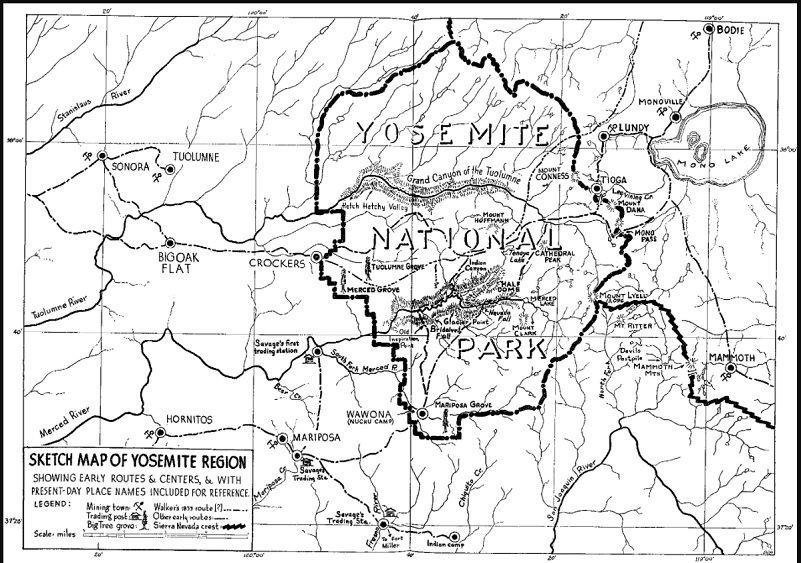

The sketch map shows the Yosemite National Park Boundary as of 1946, which at one time included Mount Ritter and the present Devils Postpile National Monument.

Sources:

Dubel, Zelda Garey, To Yosemite by Stage, Zulu.com, Third Edition, 2011.

Sargent, Shirley, Wawona’s Yesterdays 1961

Wawona’s Yesterdays (1961) by Shirley Sargent

Wawona Road (HAER No. CA-148) written historical and descriptive data Wikisource

Rare brochure for Yosemite Stage Co. 1900

Yosemite National Park Digital Archives

Yosemite National Park Statistics

Rules and Regulations Yosemite National Park, United States National Park Service, 1925

In the Heart of the Sierras by James M. Hutchings (1888)

Sierra National Forest ORV Maps

Prior Blogs in this Area:

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill, Sunny Meadows Fall Color Loop November 4, 2021

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill, Sunny Meadows to O’Neal’s Meadow Loop May 18, 2021

Walking up a Dirt Road: Westfall Picnic Area up Miami Mountain Road April 27, 2021

Walking Up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to 4S04 Miami Creek Headwaters April 20, 2021

Walking Up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to 6S09B Above Old Miami Mills January 17, 2021

Walking on a Dirt Road: Elliott Corner to Cold Spring Loop December 30, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Westfall Picnic Area up Miami Mtn Road June 2, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill Loop Along Sunny and O’Neals Meadows May 20, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to O’Neals Meadow Loop May 5, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to the Lone Sequoia April 28, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to Pilot Peak April 22, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to O’Neals Meadow April 15, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill to Sunny Meadows April 10, 2020

Walking up a Dirt Road: Worman’s Mill and Beyond March 31, 2020