MARIPOSA COUNTY – When the Ferguson Fire was first reported just before sundown on Friday, July 13, initial estimates by the first units at scene reported it at about 100 acres. It was burning in extremely steep terrain through very dry fuels, and the Sierra National Forest is ground zero for tree mortality.

Within 24 hours it had grown to 1,000 acres, and 12 hours later, was estimated at 4,000 acres. So how is a fire this intense and this large managed? One of the tactics used is to conduct firing operations.

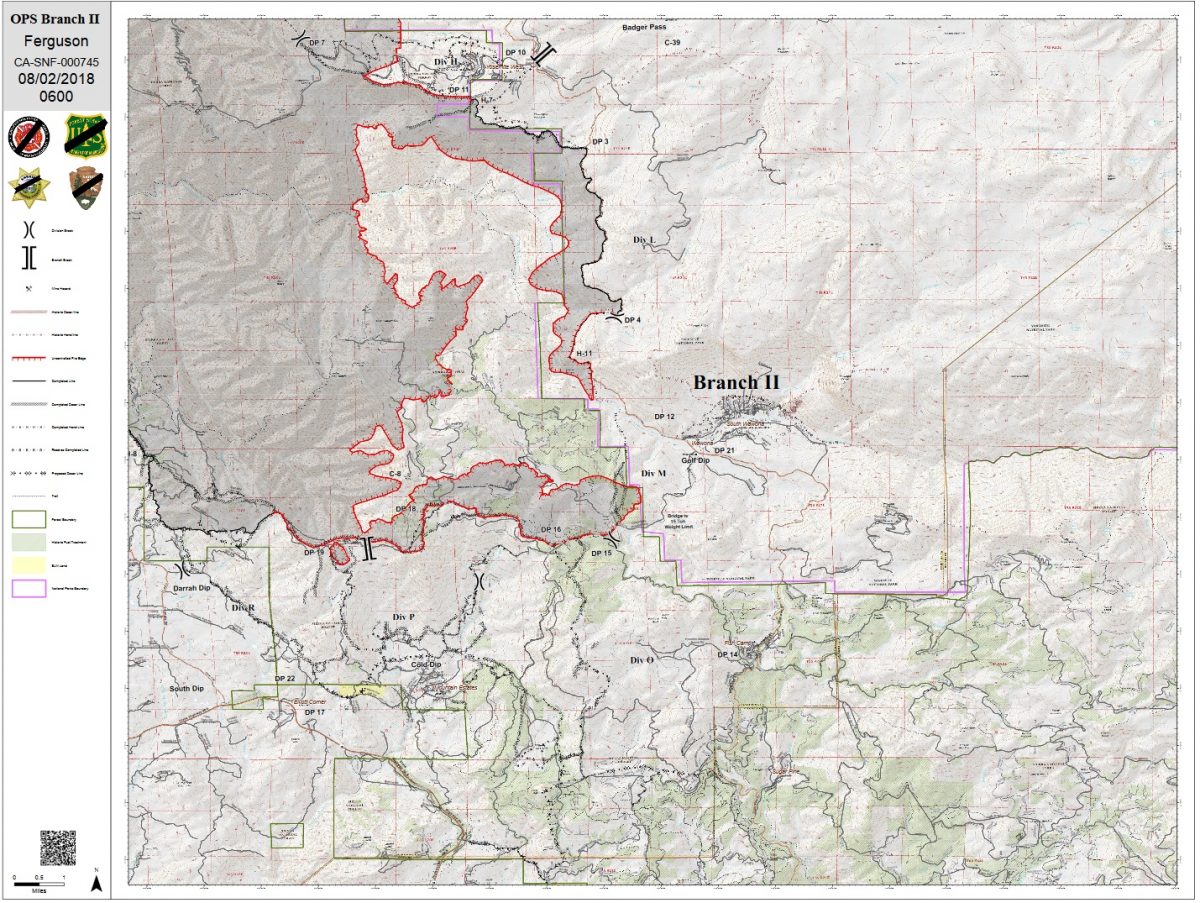

Over the last several days, crews on the Ferguson Fire have been engaged in firing operations on three sides of the fire, to widen the contingency lines and remove fuels as the active edge of the fire approaches.

So why was Highway 41 inside Yosemite National Park chosen as the eastern perimeter? Why didn’t they attack the fire farther to the west instead of letting it burn so far? And why do containment numbers seem so slow to increase?

Jake Cagle, Operations Section Chief for California Interagency Incident Management Team 4 – the team managing the Ferguson Fire – took the time to answers some of those questions. (see map below for Highway 41 branch).

We started with why they chose Highway 41 inside Yosemite for the eastern fireline.

“The topography west of Highway 41 is extremely steep, it’s rugged, it’s inaccessible, and if we did put crews in there, we couldn’t support them,” says Cagle. “Logistically, we couldn’t support them because the area has been under a heavy inversion the whole time. Tactically we couldn’t support them because we couldn’t get aircraft in there to hold all the work they would be doing.”

There are a few roads and trails across the area, but Cagle says they don’t line up with the topography they would have needed to construct effective fireline.

Another reason he cites for not attempting direct attack west of Highway 41 is the tree mortality.

“That’s a huge issue,” says Cagle, who has over 25 years of experience fighting fire. “The tree mortality produces fire effects we’ve never seen before. Fire is burning in a completely different way, and this is being considered a new fuel type. You can’t calculate fire behavior with these fuels; it doesn’t fit the current model. You don’t want to put firefighters down in there.”

Using Highway 41 as a fireline was also a good option because the crown spacing between the trees is open, says Cagle, so it didn’t “torch out” when they put fire on the ground.

“We got really good fire effects in there,” he says. “The fire cleaned up all the stuff on the ground and didn’t get up into the living trees. There are likely a couple pockets where it burned up into the dead trees, but the fire basically stayed on the ground.”

Cagle says those firing operations resulted in a “backing fire” that eased down off the mountain. That will prevent the active edge of the fire moving toward Highway 41 from rushing up the mountain, throwing embers across the line, which is now 1,000 feet wide in some spots, over a mile wide in others.

Planners estimate it will take about two days for the leading edge of the fire to reach the containment line west of Highway 41, which has given them a good window to complete firing operations. They have been prepping this line for nearly two weeks, removing hazard trees and laying down retardant along the “green” side of the line (on the east toward Wawona).

“When it burns together, it will probably be a little hotter in the middle,” says Cagle. “Fire draws its own, so as the activity heats up as the fires come together, they suck each other in.”

If the fire “gets hung up,” and stops before the fuels are consumed, managers may opt to do aerial firing from helicopters to clean it up and stop any continued smoldering that will keep putting up smoke. This involves using Plastic Sphere Dispensers (PSDs), which are balls filled with potassium permanganate that ignite when they hit the ground and fire off the fuels that haven’t been consumed.

On the southern perimeter of the fire near Roundtree Saddle, planners have been challenge repeatedly by fuel loads and weather as they constructed fireline and prepared for firing operations.

“Initially we go in and punch in the indirect line [fireline that’s out away from the active fire’s edge],” says Cagle. “After we cut dozer line, we then have to go in and do hazard tree mitigation and take out as many trees as we can that would impact the firing operation. If fire would get up into a dead tree and throw embers, we take that tree off the line.”

The slow progress at Roundtree Saddle was largely due to the fuel loads in the burn scar of the 2008 Oliver Fire.

“There were snag patches, old trees, dead trees – all hazard trees,” says Cagle. “It was an overwhelming amount of work and we had fallers and equipment in there trying to mitigate the danger to crews during the firing operations. We had the dozer line cut in there for several days, but it slowed everything down because we had so much prep work to do.”

Planners are now dealing with a large spot fire between El Portal and Yosemite West, that is pushing east through rugged terrain and is now part of the main fire.

“Henness Ridge in that area is a razorback ridge that’s not very accessible for hand crews,” says Cagle. “It’s tough to get safety zones in there and not really a place you’d want your crews to be.

“Up until a few days ago, the fire had minimal activity, and we didn’t want to fire that ridge if we didn’t have to. It could have potentially sat there doing nothing. If we had gotten open air, we would have used tankers and water drops. But now it’s forced our hand, and we’re ready for it. We established a trigger point, which was Zip Creek. It’s hit that trigger point and now it’s starting to get some heat and intensity, so we’re conducting firing operations there.”

One important member of the team for firing operations is the Fire Behavior Analyst. On California Team 4, that is Rob Scott.

“My job is to take weather forecasts and combine that with fuels and topography,” says Scott. “How dry are the fuels? What is the condition of the fuels? How steep and high are the mountains? Then I create a forecast for how the fire is going to burn on the landscape for any given time or day.”

Scott provides firefighters on the line with updates throughout the day, and notifies them when conditions are about to change – information that can affect any planned burning. His fire behavior forecasts have been a critical component to the firing on Highway 41.

“One of the benefits of putting fire on Highway 41 is that it will reduce the length of time that the fire is burning, and reduce its overall size. Also, as we move through time into August and September, the severity and intensity at which the fire will burn will continue to increase. So if this fire were on the landscape in September, it would have been to Highway 41 in a few days. We’ve looked at models and that is a high probability. We can sit on it and wait for it to get to Highway 41, or we can say right now is a pretty good time to burn because the likelihood of a spot across 41 is less than it will be in a couple weeks or a month. The effects of that fire are reduced, and there will be less of an impact on the live trees that are standing.”

Some of the firing operations on this fire have been postponed because the humidity was too high, which seems counter-intuitive.

“So the way fire moves across the landscape, there has to be fine fuels – pine needles and tiny little sticks to move the fire around to logs and bigger branches to really create flames. Fine fuels are very sensitive to changes in relative humidity. When relative humidity goes up, the amount of moisture in the fine fuels goes up. When you apply fire to fuel the first thing that happens is the fuel heats up and it dries out the water vapor. That energy is going into drying out that fuel and not making combustible gases.”

Scott says the magic number for humidity is between 30 and 35 percent. Once it goes above 35 percent, the fire doesn’t move as well and the fuels won’t been efficiently consumed. Conditions need to be right for effective firing operations.

“The primary objective is to stop the spread of the fire,” says Scott. “The secondary objective is to not get the fire so hot that it throws spot fires across the line, so there’s a balance.”

Every meadow, every canyon, every ridgetop in the very large footprint of this fire has its own unique weather conditions. For example, one big challenge for crews has been the northerly winds out of Devils Gulch in the late afternoon and evening. Scott says they stopped putting fire on the ground at about 3 p.m., allowing the fire to burn down before the winds came so as to avoid ember cast toward Ponderosa Basin.

The final question for Operations Section Chief Jake Cagle was about containment. Why is that number hanging around in the 30+ percent range for so many days?

“It’s tough to continue containment when fire is growing within itself,” says Cagle. “We had one day where we contained five miles of line, but the fire made such progression on the interior – because that counts, it’s consumable acres – that shrinks the percentage.”

A section of fireline is moved into the “contained” column and indicated by a black line on the map when officials are confident that it’s secure and there is no chance for a flare-up that would threaten life or property. That doesn’t mean there isn’t line around the whole fire.

Footman Ridge is a good example of caution when it comes to calling something “contained.”

“We’ve been battling that for days and it’s pretty cold,” says Cagle. “But we’re waiting and waiting because we’re still apprehensive. We still get that north wind in the evening, and even had a spot there Tuesday night, but it was picked up quickly. We have to be sure it’s secure before we put black on it.”

Jake Cagle has been a member of the California Interagency Incident Management Team 4 since 2007, and is a Fire Captain at the Kern County Fire Department.

Rob Scott is a Fuels Officer on the El Dorado National Forest and is from Diamond Springs, Calif.