“One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor.” – Paul Simon

Spring: it brightens the heart and stirs the blood. The birds are singing, the flowers are blooming, and the air smells sweet. I love spring.

It is a pretty great time for a biologist. Running around photographing wildflowers and bugs makes me really happy. However, the onset of spring also marks the end of mushroom season.

Many of the fungi around here only reproduce (via mushrooms, etc.) when there is sufficient water. And that means during the rainy season, which is from fall through spring for us, since we live in a Mediterranean climate.

So, while we are saying hello to fresh flushes of orange California poppies, pink western redbud, and violet wild hyacinth, we might stop for a moment to appreciate the humble fungi.

Kingdom Fungi

These amazing life forms make up an entire biological kingdom, Fungi. Humans are assigned to the kingdom Animalia, grouped along with everything else we consider an animal (from fleas to whales). Kingdoms are very broad categories that include a wide range of life forms within them.

Fungi are a hugely variable group, but many live via thready networks of mycelia (underground, within trees, etc.), and help move nutrients from decaying things, through the soil and, in some cases, into the very roots of the flowering plants we admire in spring.

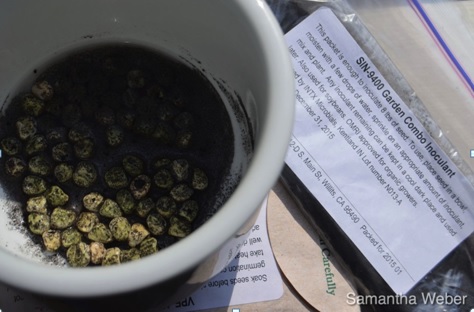

Many smart gardeners add mycorrhizal fungi to their garden soil, or soak their seeds in a mycorrhizal slurry before planting them. That way the seeds already have fungal allies nearby to help them get more nourishment from the soil. This can lead to healthier, larger, more disease resistant plants in your garden, all of which all sound great to me.

Many smart gardeners add mycorrhizal fungi to their garden soil, or soak their seeds in a mycorrhizal slurry before planting them. That way the seeds already have fungal allies nearby to help them get more nourishment from the soil. This can lead to healthier, larger, more disease resistant plants in your garden, all of which all sound great to me.

Mycorrhizal slurry soaking the peas, so they’ll be healthy, strong, and productive.

My Fungal Friends

I am a fan of fungi.

Many people love to learn about mushrooms in order to find and harvest and eat the edible ones. I don’t care if it’s edible. If it’s tiny and slimy and poisonous, I’m still excited to meet it.

On a one-day mushroom course I took (at Point Reyes National Seashore), the teacher would sigh when I’d bring mushrooms I’d found for him to identify.

This is because he, like so many mushroom gurus, had a strong bias toward edible mushrooms. This is normal in the mushroom world.

Then I’d bring him a mushroom as tall as an almond that I’d found growing inside a rotting log. This is not normal in the mushroom world.

Frequently the first verbal response I’d get (if you don’t count the sigh) was a tired look and, “Samantha…”

The next answer I usually got, after he turned the unknown in his hand, and referred to a few books, was, “Well, I’m not sure.”

The mushroom book I own, Mushrooms Demystified, by David Arora, is surprisingly entertaining, but is over 900 pages long, and describes over 2000 species.

Therefore, many of the photos I will be showing you are of species I have not identified.

My goal is to promote mushroom appreciation. To encourage taking a moment while you’re weeding the garden, raking leaves, and otherwise living your life, to stop and peer at these humble allies of ours.

So, here are a few of the delightful fungi I’ve encountered on our property. You may have many of the same kinds where you live.

Please feel free to comment if you’ve seen any of these in your neck of the woods, or if there are other fungi you’ve noticed that you are curious about.

Earthstars — oh my

A beautiful, olive-colored earthstar fungus.

A beautiful, olive-colored earthstar fungus.

I have a confession: I’m slightly obsessed with earthstars.

Specifically, I’m in love with the hygrometric earthstars (Astraeus hygrometricus) that we have on the edge of our driveway, growing under an oak tree. This species amazes me. It’s so dramatic!

When it’s dry outside, these little fruiting bodies are either underground, or are hard, dry little things, looking like old leather. You really have to look closely in leaf litter to even see them.

Earthstar fungus fruiting body, all dried up, in leaf litter.

However, just add water, and what a transformation! The little ball unfurls completely, to reveal a star-shaped beauty. The sections flare out and arch back to push against the ground and raise the spore sac up (if the individual is fresh enough to still have a spore sac). Presumably the result is that during rainy, or otherwise fungus-friendly conditions, the lifted spore sac is then better able to catch any passing breezes, thus scattering the spore cells of tomorrow’s earthstars far and wide.

However, just add water, and what a transformation! The little ball unfurls completely, to reveal a star-shaped beauty. The sections flare out and arch back to push against the ground and raise the spore sac up (if the individual is fresh enough to still have a spore sac). Presumably the result is that during rainy, or otherwise fungus-friendly conditions, the lifted spore sac is then better able to catch any passing breezes, thus scattering the spore cells of tomorrow’s earthstars far and wide.

Photo I took of earthstar fungus to record their size, to help identify them to species.

Photo I took of earthstar fungus to record their size, to help identify them to species.

And to that, I say, Hooray!

I am pretty sure I saw them two years ago, but thought, “Naw, that can’t be that super cool fungus I’ve seen pictures of… it’s probably just an exploded acorn.”

This winter I spied them again, and thought, “Well, maybe it’s that super cool fungus…” and actually Googled “germinating acorns” just to see if they looked at all like what I’d seen.

They did not.

Germinating acorns look pretty much like acorns, but with a little root going down into the ground. Go figure.

They do not burst open from the tip and end up in a star shape. That would be an earthstar.

They do not burst open from the tip and end up in a star shape. That would be an earthstar.

Earthstar fungus fruiting body (without spore sac) showing just how much they can look like exploded acorns.

So, this year I finally knew I’d seen earthstars, and then learned, through tracking their changes between wet and dry weather, that ours were hygroscopic (water-absorbing) earthstars. So very cool.

I strongly encourage you to head out next fall after it rains to look for these dramatic fungi. They can be pretty hard to spot, but it is worth it.

And the worst thing that might happen is you’d see some other cool fungi. For example…

Bird’s nest fungus–so cute, so athletic

What a great little fungus.

I’m not certain which species we have, they form an entire family of fungi (Nidulariaceae), but it’s clearly a bird’s nest fungus. In the bird’s nest photo I have, you can also see, attached at the mushroom’s lower left, another fruiting body that still has its “lid” on. That lid will come off later to reveal more of those egg-like spore sacs.

This tiny thing could fit on a dime with room to spare. I found it growing at the base of miner’s lettuce (Claytonia spp.) in my iris bed.

This tiny thing could fit on a dime with room to spare. I found it growing at the base of miner’s lettuce (Claytonia spp.) in my iris bed.

You can see a video of this fungus developing over eight days, sped up to 47 seconds, thanks to Cornell University’s “Cornell Speedy Bio” and YouTube.

The way this tiny fungal fruiting body works is just too cool.

I’m summarizing, but when the “nest” (called a peridia) gets hit by a raindrop in a storm, it flings the “eggs” (called periodoles) into the air. The “eggs” are attached to the cup by a long tube which detaches from the cup during this event.

The cup-end of the tube is sticky, so when the periodoles & their tubes are flying through the air, the sticky end might attach (for example) to a stem or leaf of a plant, so the eggs and stem are stuck on something above-ground.

At some point thereafter, the spores are then released from the “eggs” from a (hopefully) lofty perch to disperse far and wide, spreading the joy of these tiny little constructions into the future.

What this means: the “bird’s nest” acts as a teeny tiny catapult, powered by a raindrops.

Powered by raindrops?!? Yes.

Can you see why I love fungi?

Turkey tail–neither turkey nor tail

A common fungus a lot of people are familiar with is called turkey tail–it tends to grow on dead trees (Arora 1986), including stumps. This photo shows one growing on a Ponderosa pine stump in our yard.

There are several species of turkey tail, but I think this one is hairy turkey tail, Trametes hirsuta. The species name, “hirsuta,” is from the word hirsute, which means hairy. How very logical!

Turkey tail fungus (possibly hairy turkey tail) looking rather elegant on a Ponderosa pine stump.

Turkey tail fungus (possibly hairy turkey tail) looking rather elegant on a Ponderosa pine stump.

Purple-spored puffball: it’s purple

Years ago, my husband had been doing yard work and said there was something I needed to see. He walked me to the edge of our property and lo, there was a puffball fungus.

Now, I’ve seen puffballs before. I don’t mean to brag or anything, but I am a card-carrying biologist, and while I still think each and every puffball is special, I’ve seen more than a handful in my lifetime.

A rather typical looking puffball fungus on our property.

A rather typical looking puffball fungus on our property.

But, I’d never seen a purple puffball before.

So, very excited about this purple puffball, I ran back to the house and started flipping through my beloved Mushrooms Demystified (Arora 1986).

In that mushroom bible, I happen upon a black and white photo that looked promising, and read, “mature specimen in which the outer layer of the peridium (spore case) is disintegrating.” (Arora, p. 687)

Disintegration is a great description of the outer layer of that puffball. So far, so good.

Then I read: “The purplish color of the mature spores is the most distinctive characteristic of this species.”

Then I read: “The purplish color of the mature spores is the most distinctive characteristic of this species.”

Woo-hoo! I didn’t need a microscope to tell me that the dusty stuff (spores) was decidedly purple.

So, while I frequently have to be content to not figure out what species of fungus I’m looking at, this time I felt confident.

Houston, we have purple-spored puffball (Calvatia cyathiformis)!

In the last two years I’ve traipsed around the property trying to find that purple beauty again. Alas, to no avail. I will continue to try and find it each fall, but I am glad to know that I’ve seen it at least once, and I knew it by name.

I don’t know your name, but I know I like you

Here are more mushroom images taken from around our property, none of which I actually have identified, but all of which I share to encourage you to look around your world for cool fungi growing here and there.

Enjoy!

Beautiful little pink mushrooms I found under a manzanita brush pile.

Beautiful little pink mushrooms I found under a manzanita brush pile.

This was a mid-sized, translucent mushroom I found growing just downhill of our garden. I think it’s an inky cap mushroom (see http://www.mushroomexpert.com/coprinoid.html), but that doesn’t narrow it down much.

Inky cap mushrooms are characterized by having mushroom caps that curl up and liquefy (thus spreading spores via that liquid). However, it seems that the various mushroom species that share this adaptation may not be closely related at all.

This is a great example of how much biologists don’t know about all the life on our planet. It’s rather mind-boggling how little we understand about how it all works.

This is a great example of how much biologists don’t know about all the life on our planet. It’s rather mind-boggling how little we understand about how it all works.

But, that’s also why it’s never boring.

My husband discovered these pretty little gray-capped mushrooms last weekend, growing in under a pile of decaying cut grass. They look a bit like young shaggy mane mushrooms (Coprinus comatus; see Laws 2007, p. 16).

The next five shots are of a really big mushroom I photographed over eight days.

Day 1 photo of mushroom, with gardening glove for scale.

Same day, shot from the side. It’s barely out of the ground.

Same day, shot from the side. It’s barely out of the ground.

Two shots six days later: the mushroom cap has unfurled, and revealed itself to be quite large (more than five inches across).

Two shots six days later: the mushroom cap has unfurled, and revealed itself to be quite large (more than five inches across).

Side view clearly showing that it has gills underneath the cap. Some mushrooms have pores, not gills, so this is an important distinguishing characteristic to note.

Blurry shot on same day with lens cap for scale. Big mushroom!

Blurry shot on same day with lens cap for scale. Big mushroom!

Day eight: mushroom cap is starting to curl upward–this is to help the spores that lie in between the gills catch a breeze and disperse. This is the last photograph I took of it.

Day eight: mushroom cap is starting to curl upward–this is to help the spores that lie in between the gills catch a breeze and disperse. This is the last photograph I took of it.

Pretty little peach-colored mushrooms. You can just see the edges of gills on the bottom left of the larger one.

Pretty little peach-colored mushrooms. You can just see the edges of gills on the bottom left of the larger one.

There are also some seriously tiny mushrooms.

These last mushrooms were growing in the deep leaf litter under one of our largest live oaks. There’s all kinds of biological goodness down there.

I loved this little white mushroom. I had to squat down really low to take a photograph.

Little white mushroom–note the size of the live oak leaf, and blades of grass.

Little white mushroom–note the size of the live oak leaf, and blades of grass.

The top was slightly fluted, almost ruffled–very pretty.

Then I took a photograph of it from the side, so I could record the texture of the stem (in case I tried to identify it later).

Tiny white mushroom from the side, focused on the stem texture.

Tiny white mushroom from the side, focused on the stem texture.

Yes, my head was in the litter at that point. Ah, the glamorous life of a biologist.

That is when I spied an even tinier mushroom, right behind the first teeny mushroom, this one hiding under a live oak leaf.

That is when I spied an even tinier mushroom, right behind the first teeny mushroom, this one hiding under a live oak leaf.

Very bashful mushroom.

That was a really tiny mushroom.

But it is not the smallest I’ve seen. One of the smallest I’ve photographed is this last one. Note the size of the live oak leaf and the sharp, pencil-looking thing.

But it is not the smallest I’ve seen. One of the smallest I’ve photographed is this last one. Note the size of the live oak leaf and the sharp, pencil-looking thing.

That pencil-looking thing is the tip of a pine-needle.

This is what I love about biology. If you just stop, take a moment, and quietly look around, you will start to see all kinds of things that you’d never noticed before.

And with that, I wish you happy hunting, and encourage you to refrain from eating any of the mushrooms you find, ok?

Even mycologists are very careful about eating them. Words of wisdom I’ve heard direct from mushroom experts:

There are old mycologists,

and there are bold mycologists.

But, there are no old, bold mycologists.

References

Books

Aurora, David. 1986. Mushrooms Demystified. 2nd ed. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, California.

Laws, John Muir. 2007. The Laws Field Guide to the Sierra Nevada. California Academy of Sciences, Berkeley, California.

Websites

www.mykoweb.com

David Fisher’s Interactive key to the genera of gilled mushrooms of North America, from the book Mushrooms of Northeastern North America.