Article written by Laurie Waskin of the Reel Cowboys. Special thanks to Kathryn Ellis, Chairperson of the North Fork History Group, for additional information.

NORTH FORK — “North Fork” – the evocative name bestowed upon this idyllic 19th century town may sound familiar to western enthusiasts, along with an assumption the locale could have been coined by screenwriters similar to The Roy Rogers Show fictional setting of “Mineral City” and other productions. But this real-life community in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada has even distinguished itself on a variety of fronts that tie North Fork into some significant and fascinating California history.

In addition to its beginnings as a major supplier of lumber for the gold rush towns, in recent years North Fork has also earned a measure of fame from its official title “Exact Center of California.” Established by both the United States Geological Survey and Fresno State University’s Engineering and Surveying Department in 1995, this intriguing and celebratory theme was also the focus of a visit by Huell Howser for a PBS episode of California’s Gold.

In addition to its beginnings as a major supplier of lumber for the gold rush towns, in recent years North Fork has also earned a measure of fame from its official title “Exact Center of California.” Established by both the United States Geological Survey and Fresno State University’s Engineering and Surveying Department in 1995, this intriguing and celebratory theme was also the focus of a visit by Huell Howser for a PBS episode of California’s Gold.

Besides these notable assets under its belt, although a small town in breadth North Fork has left big footprints in the western genre of television and film history where it struck another kind of gold thanks to screenwriter and director Sam Peckinpah. A Fresno native, the youthful Peckinpah regularly spent a good deal of time in North Fork where his grandparents resided. The enjoyable experience left Peckinpah with many strong impressions and recollections, which he often made use of as an adult in his TV westerns and film work. One standout example was fondly casting the name of the town as the setting for television’s The Rifleman, – albeit in New Mexico Territory vs. the factual California.

Both sides of Sam Peckinpah’s family were firmly based in North Fork. Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Peckinpah and their sons arrived in 1884 and Peckinpah Mountain is named for the location where the family’s hard working sawmill once stood. However, by the turn of the century the Peckinpahs had opened a hotel and store in nearby South Fork. Born to Charles’ son, David, and his wife Fern Church Peckinpah in 1925, Sam grew to love the cowboy way at his maternal grandfather Denver S. Church’s North Fork cattle ranch, where his father served as foreman. Many hired hands also had forebearers who’d been miners and ranchers during the 19th century and often had interesting tales to spin. Sam much preferred this latter day Old West lore and its vanishing lifestyle to his city home in Fresno, although the boy’s grandfather’s other vocations meant he was not always on site. A righteous man, Church was a practicing attorney and at various times served as a Superior Court county judge, district attorney and U.S. Congressman. Church was additionally well known throughout the Sierra Nevada for his shooting expertise.

Peckinpah later based some of his characterizations and plots on his North Fork years and drew from this as a screenwriter and director of western TV series like Gunsmoke, Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre, Have Gun – Will Travel, Broken Arrow, and The Rifleman. Although it wasn’t just the town’s name Peckinpah borrowed for his creation of The Rifleman – there were other semi-autobiographical undertones. The popular show, which originally ran from 1958-1963, starred Chuck Connors as Lucas McCain and Johnny Crawford as his son Mark, who made their home on a cattle ranch outside town during the 1880s. Like Peckinpah’s grandfather, Lucas found himself regularly called upon to uphold the law in various ways, often with the town sheriff. It didn’t hurt that in another parallel, Lucas was also widely recognized as an excellent shot. Interestingly, this classic western, which continues in syndication today, was actually the result of Peckinpah’s rejected screenplay for Gunsmoke. Following some revision, he sold the episode to Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre where it turned into a pilot for The Rifleman. Peckinpah wrote and directed some episodes but went on to other projects after the series first year, including films like Ride the High Country (1962) and The Wild Bunch (1969).

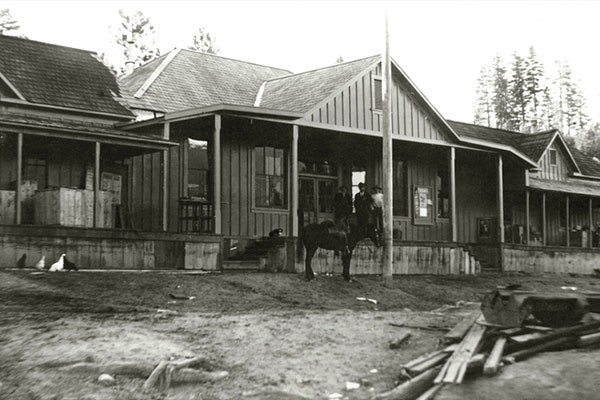

Although the lines can sometimes blur between imagination and reality on-screen, the real North Fork that left such an impression on Sam Peckinpah and others definitely has its own illustrious past. Here’s a peek at life in North Fork during its historic heyday, when the town’s booming lumber industry was strongly intertwined with the reign of the California gold rush, benefiting all.

Established in the mid-19th century, the settlement took its name from a location then known as the North Fork of the San Joaquin River. However, this was later revealed as a misnomer since the rambling waterway turned out to be Willow Creek, which originated at Bass Lake. Yet the genial name stuck and the rural community became an important main source of lumber for the mining towns.

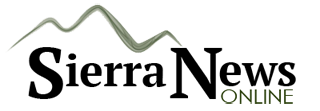

The first cabin in North Fork was built by miner Milton Brown, who ran a supply center there for fellow miners and stockmen. During the 1870s, as the town grew, the Fred and Geo Driver store and stage stop building were constructed and still stand today. The town also boasted several saloons, a blacksmith shop and livery stables. Sheep were commonly brought through North Fork to reach the plentiful acorns at higher elevations, while ranchers led their cattle there, too, during the summer months. Some of the cow camps can still be seen today.

Additional sawmills sprang up in the area, though smaller than the Peckinpah enterprise. Other prominent residents were Judge Klett and families such as Bigelow, Ellis, Teaford and Bethel.

Although generally a peaceful town, there were the occasional feuds and killings, as in other mining era hamlets. So to keep order, Sheriff John M. Hensley of Fresno County was the lawman with the power to make arrests in the latter part of the 19th century. Whenever things got rough, Sheriff Hensley diligently traveled up from Madera and if required, the nearest courthouse was located a further 30 miles away in Belleview. A little more convenient was the shared jail at O’Neals, a mere 12 miles distant and built from 2 x 4’s and 60 penny nails. This jail once held an unusual occupant – a local rattlesnake, resulting in a curious official inquiry about its floorboards. The incident occurred after Sheriff Hensley’s arrest of a man for disturbing the peace at an Easter picnic, who was brought to the jail. A deputy was then instructed to stop by and check on the overnight prisoner, which did not occur. Nevertheless, it turned out the inmate had an unexpected and fearsome companion – who may have been as startled as the man it kept company with all night – when at daybreak the deputy opened the door to reveal a coiled rattler waiting on the other side, blinking at him. Luckily, the prisoner had not been harmed and was released. But the incident sparked a grand jury investigation into how a snake could’ve made its way inside an incarceration facility, effecting an order to the Board of Supervisors by the State Board of Charities and Corrections to cease using the jail.

But this odd tale didn’t end there. Some years later, the unoccupied jail building was itself the object of a successful heist. In the middle of the night, it was hoisted onto a truck and driven away by several North Fork residents, whose town lacked its own jailhouse. This apparently solved the dilemma as the “stolen jail” remained in North Fork for many years afterwards and now resides in Bandit Town.

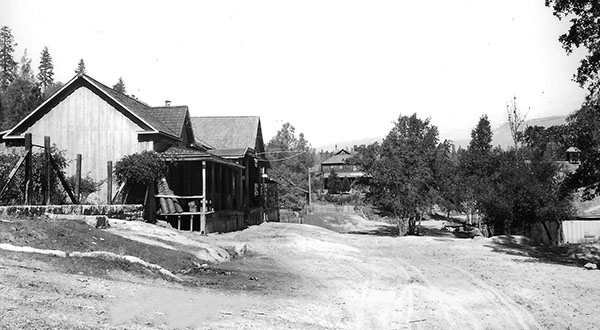

Today residents are proud of their Old West history, gold rush era roots, and rich logging heritage – the latter celebrated at an annual summer Logger’s Jamboree. The well-known Sierra Mono Indian Museum and Cultural Center is also in town. In addition to North Fork’s own historic buildings, which includes the Buckhorn Saloon (built 1923), Bandit Town is also close by to offer a taste of the Old West. It features the original O’Neals/North Fork jail and some typical cowboy buildings that include a saloon and dance hall, shops, a corral/rodeo arena, guest rooms, and wedding chapel. Visitors can feel as if they’ve stepped back into the past – or at the very least, a western TV or movie set. Bandit Town is currently open as a performance and event venue.

Today residents are proud of their Old West history, gold rush era roots, and rich logging heritage – the latter celebrated at an annual summer Logger’s Jamboree. The well-known Sierra Mono Indian Museum and Cultural Center is also in town. In addition to North Fork’s own historic buildings, which includes the Buckhorn Saloon (built 1923), Bandit Town is also close by to offer a taste of the Old West. It features the original O’Neals/North Fork jail and some typical cowboy buildings that include a saloon and dance hall, shops, a corral/rodeo arena, guest rooms, and wedding chapel. Visitors can feel as if they’ve stepped back into the past – or at the very least, a western TV or movie set. Bandit Town is currently open as a performance and event venue.

Whether you’re en route to Yosemite’s south entrance, are curious about what the official “Exact Center of California” looks like, appreciate Old West history or a western TV and movie buff, or perhaps just want to enjoy the stunning natural beauty of the area – North Fork beckons.

And it’s still a small, friendly town – just like the one its most famous resident, Sam Peckinpah, nostalgically brought to life for millions of people on-screen.

All images courtesy of the North Fork History Group.

Check out this great video about the making of Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch!”