We had the trail and amazing views all to ourselves. From Mount Watkins, it felt like we could almost reach out and touch Half Dome, Clouds Rest, and Tenaya Canyon. Well, kind of . . .

Where: Yosemite National Park

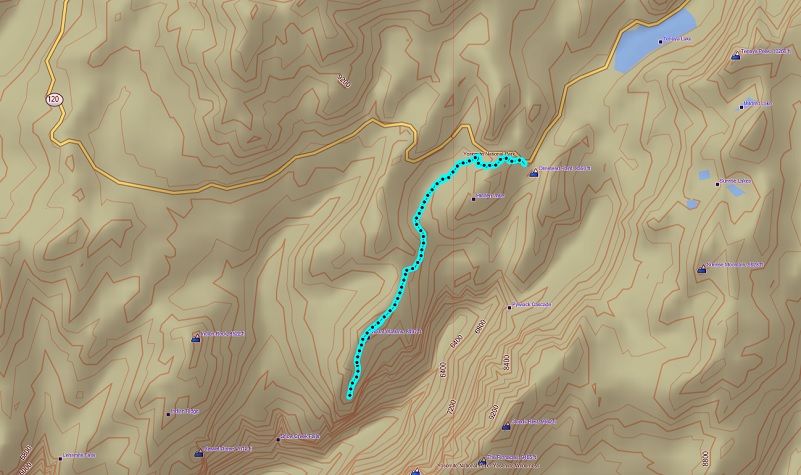

Distance: 8.6 Miles

Difficulty: Easy to Moderate

Elevation Range: 7,996′ – 8,497′

Date: November 12, 2019

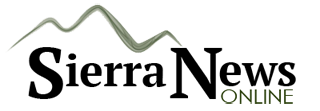

Maps: Falls Ridge, Hetch Hetchy Topographic Quad Maps

Dog Hike? No, dogs not allowed in Yosemite National Park Wilderness

Tioga Road was still open and we felt we needed to get our hikes off of Tioga Road in before weather ended our opportunities up there. We were the only vehicles when we parked at Olmsted Point and the temperature was about 46 degrees when we left the car. It turned out we were the only one on this trail on this day! The trail starts at the west end of the parking lot where you walk alongside the road for a short distance, then the trail leads down along the west side of the rocky knob that is Olmsted Point. The trail then follows a “path” over the granite slab lined with boulders.

The trail wasn’t signed but was well used when we hiked it but that is not always the case. If you are hiking it early in the season, the first part of the trail can be easy to lose as it crosses the granite slab but that part of the trail was well marked by a boulder border on the day we hiked it.

On past hikes we have taken a slight detour along the trail to Hidden Lake. I have included a topographic map with our track to Hidden Lake at the bottom of this blog in case you are interested in taking this side trip which is off trail and unmarked. I suggest you have a map and have map reading skills to use it if you want to try this. We stayed on the main trail today which led us along the rim, high above Tenaya Canyon.

The trail to Mount Watkins splits off of the main Snow Creek Trail that goes down to Yosemite Valley and you need to pay attention to that spot at about the 3 mile mark because it is not marked. The trail to Mount Watkins will veer off to the left as you leave the views of Tenaya Canyon. The Mount Watkins spur leads up the granite, staying on the high point or “ridge” of the dome. The trees start to open up and you just know that you will be getting close soon.

After about .8 miles from that trail split, you reach the high point that is Mount Watkins, chock fill of views.

There are a couple of explanations for the meaning behind Mount Watkin’s name. According to Josiah Whitney, the Indian name was “Waijau“, meaning “pine mountain”. Ansel Hall translated “Wei-you” the name given in his guide book, as meaning “juniper mountain.”

But there is another and much different story. Yosemite Place Names says that Mount Watkins is named after Carleton E. Watkins, an early day Yosemite photographer of wide fame. Born in New York in 1829, the oldest of eight children. His parents were John and Julia Watkins, a carpenter and an innkeeper. Born in Oneonta, New York, he was a hunter and fisherman, was involved in the glee club and the Presbyterian Church Choir.

In 1851, Watkins and his childhood friend Collis Huntington moved to San Francisco with hopes of finding gold. Although they did not succeed in this specific venture, both became successful. Watkins became known for his photography skills, and Huntington became one of the “Big Four” owners of the Central Pacific Railroad. This would later be helpful for Watkins.

During the first two years in San Francisco, Watkins did not work in photography. He originally worked for his friend Huntington, delivering supplies to mining operations. He then worked as a store clerk at a George Murray’s Bookstore, near the studio of Robert Vance, a well-known Daguerreotypist. An employee of Vance’s unexpectedly left his job, and that led to Watkins working at the studio.

Before his work with Vance, Watkins knew nothing about photography. Vance showed him the basic elements of photography, planning to return and retake the portraits himself. However, when he came back, he found that Watkins had excelled at the art while he was away and his customers were satisfied.

By 1858, Watkins was ready to begin his own photography business. He did many various commissions, including “Illustrated California Magazine” for James Mason Hutchings and the documentation of John and Jessie Fremont’s mining estate in Mariposa. He made Daguerreotype stereoviews (two nearly identical images of the same scene, viewed through a stereoscope to create an illusion of depth) at the “Almaden Quicksilver Mines.” These were used in a widely publicized court case, which furthered his reputation as a photographer.

In July 1861, Watkins made the decision that changed his career when he traveled to Yosemite. He brought his mammoth-plate camera (which used 18×22 inch glass plates) and his stereoscopic camera. The stereoscopic camera was used to give the subject depth, and the mammoth-plate camera was used to capture more detail. The photographer returned with thirty mammoth plate and one hundred stereo view negatives. These were some of the first photographs of Yosemite seen in the East. In 1864 to 1865, Watkins was hired to make photographs of Yosemite for the California State Geological Survey.

In 1867, Watkins opened his first public gallery, in addition to sending his photographs to the Universal Exposition in Paris, where he won a medal. This became his lavish Yosemite Art Gallery. He displayed over a hundred large Pacific coast views in addition over a thousand images available through stereoscopes. Despite his success as an artist, he was not successful as a businessman and ended up losing his gallery to his creditor J.J. Cook.

Not only did Watkins lose his studio to Cook, he also lost its contents. When Cook and photographer Isaiah Taber took over Yosemite Art Gallery, they began reproducing his work without giving him credit. The 19th century had no copyright laws covering photographs, and there was nothing Watkins could do to combat this plagiarism. Due to this, he began recreating the images he lost, calling it the “New Series.”

Watkins met Frances Sneed when he was photographing in Virginia City. They became romantically involved in 1878 and were married a year later, on Watkins’ fiftieth birthday. The couple had two children: a daughter Julia in 1881, and a son Collis in 1883.

Watkins began to lose his sight in the 1890s. His last commission was from Phoebe Hearst to photograph her Hacienda del Pozo de Verona. Watkins was unable to complete this job due to his failing sight and health. In 1895-96, his lack of work led to an inability to pay rent. The Watkins family lived in an abandoned railroad car for eighteen months before Huntington deeded Watkins Capay Ranch in Yolo County.

Watkins kept the majority of his work in a studio on Market Street which was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, with it countless pictures, negatives and the majority of his stereo views. After this horrific loss, he retired to Capay Ranch.

Three years after Watkins retired to Capay Ranch, he was declared incompetent and put into the care of his daughter Julia. She cared for him for a year before committing him to the Napa State Hospital for the Insane in 1910, at which point Frances Watkins began referring to herself as “widow.” Watkins died in 1916 and was buried in an unmarked grave on the hospital grounds.

Watkins photographed Yosemite often, and had a profound influence over the politicians debating its preservation as a national park. His photos did more than just capture the now national park because he created an icon. Half Dome, for example, already existed, but Watkins’ photos brought it to people in a way that they could experience it. It became iconic through his photographs, and became something people wanted to see in person. His images had a more concrete impact on Yosemite becoming a national park than just encouraging people to visit. It is said that Senator John Conness passed Watkins’ photographs around Congress. His photography was also said to have influenced President Abraham Lincoln, and was one of the major factors in Lincoln signing the bill in 1864 declaring Yosemite Valley inviolable. This, then, paved the way for the National Parks system in its entirety.

Not every environmentalist believes in Watkins’ positive influence on the ideals they aim for. In addition to photographing Yosemite, Watkins also photographed one of the giant sequoia trees in California, the “Grizzly Giant.” His photo was created with one of his mammoth plates, which allowed him to photograph the entire tree, which had not been done before. Watkins, in addition to creating an image not seen before, was already very well known, and the image rapidly gained fame. Despite the fact that Watkins was attempting to preserve the trees, the way his photograph captured American audiences led to an increase in tourism in the area, which led to larger commercialization, which led to a diminishing of the giant sequoias.

I located a wonderful site that is dedicated to preserving Carleton Watkins’ photographs. The collection is extensive, well organized and searchable. Many of these images are protected in some manner, so I didn’t include them in this blog but you can go to this site to view them online The Photographics of Carleton Watkins.

We like to walk down farther to an area that overlooks Tenaya Canyon, about another .4 mile.

We picked a good spot to eat our lunch and admire the view.

We weren’t the only critter admiring the view though. This raven sat there the entire time I sat there.

It was time to head back and as I reached the top of Mount Watkins I took a look back at Half Dome.

I like to do this hike in the fall, when it is cooler and on a day that has good air quality. It is a treat to do it right after snow has fallen on the higher peaks, creating a beautiful view, but you need to watch for a good window when Tioga Road is open. Those fall storms can result in the road closing and reopening a few times before it closes for good for the winter. You can also continue down the trail all of the way via the Snow Creek Trail to Yosemite Valley or when Tioga Road is closed, come up from the valley on the trail. Lots of options related to this trail!

Dog Hike? No, dogs not allowed in Yosemite National Park Wilderness.

Doarama:

What is a Doarama? It is a video playback of the GPS track overlaid on a 3 dimensional interactive map. If you “grab” the map, you can tilt it or spin it and look at it from different viewing angles. With the rabbit and turtle buttons, you can also speed it up, slow it down or pause it.

Olmsted Point to Mt. Watkins Doarama

Map and Profile:

To hike off trail to Hidden Lake, about a half of a mile from Olmsted Point you will head south about .3 miles to reach it and we have cut back to the trail cross country to the west a bit. It is easy to get turned around out here so that is why I recommend that you have a map with you and that you can actually orientate yourself to read and follow the map. You may get lucky later in the season and find a use trail to the lake but there are all kinds of climber and use trails in this area that go other places. Just beware.

Prior Blogs in the Area:

Hiking from Olmsted Point to Mt. Watkins and Beyond November 8, 2016

Sources:

Yosemite Valley Place Names (1955) by Richard J. Hartesveldt