I had heard of the Racetrack at Death Valley and its mysterious moving rocks, but the stories that I had heard of the washboard road and that 3 1/2 hour drive had not put this adventure on my list until now. We rented a jeep for the day and took it where I didn’t want to take my personal vehicle. Why did I wait so long to do this? The views were stunning!

Where: Death Valley National Park

Date: February 28, 2018

We stayed at Stovepipe Wells for a few days, taking day trips. Our day trip to the Racerack was a long one but so worth it. We picked up our Jeep at Farabee Jeep Rentals in Furnace Creek and maximized our day with it, visiting the Ubehebe Crater on the way in and the Ubehebe Mine on the way out.

We had cooler weather on this trip, waking up to snow covered mountains lining Death Valley’s floor. We brought lots of warm clothes, stocked ice chests with our lunch, snacks, water and drinks.

The road to Racetrack Valley begins near Ubehebe Crater. Normally, it is recommended for high-clearance vehicles with heavy-duty tires as it can be rough with its share of washboards. Sure enough, that was pretty washboardy at times but we didn’t need our 4WD for this road, but those conditions can change. They don’t recommend that you take a standard vehicle out here because they often get flat tires. Off-road driving is prohibited as the desert is very fragile and vehicle tracks can remain for years. Driving offroad is strictly prohibited. Although it was cooler on our visit, it can get very hot out here in the summer. There is no cell phone coverage in the area.

About 21 miles down that dirt road, we hit Teakettle Junction. I don’t know how Teakettle Junction came to be, but they say that it tradition to bring a new teakettle and to either inscribe your message on it or to write a letter and put it in it. This is said to bring good luck to those that leave a kettle and to provide an exciting sign for future travelers. We had a good break from those washboards, checking out the teakettles and wished we had brought one to add to the collection.

As we reached Tin Pass (4,960′), we could see a forest of Joshua Trees on the hills surrounding the road. Joshua Trees actually are a type of yucca that can grow up to 30 feet tall.We also saw several types of cactus.

We continued on the road straight ahead to the Racetrack Playa which we thought we could way ahead of us but what was that white? The pictures I had seen were not white.

As soon as I got out of the Jeep, I walked over to the Playa and sure enough, that white stuff was snow.

The Racetrack is a playa, a dry lakebed, about 3 miles long and 2 miles wide. At least 10,000 years ago this region underwent climatic changes resulting in cycles of hot, cold and wet periods. As the climate changed, the lake evaporated and left behind beige colored mud, at least 1,000 feet thick.

We stopped at the south end of the Playa. We had heard that we could get the best views of the rocks and their tracks by walking toward the southeast corner of the playa. Rocks tumble off of the surrounding mountains to the Racetrack. Once on the floor of the Playa the rocks move across the level surface leaving trails as records of their movements. Some of the moving rocks are pretty big and have traveled as far as 1,500 feet. Throughout the years many theories have been suggested to explain the mystery of these rock movements. A research project has suggested that a rare combination of rain and wind conditions enable the rocks to move. A rain of about 1/2 inch, will wet the surface of the playa, providing a firm but extremely slippery surface. Strong winds of 50 mph or more, may skid the large boulders along the slick mud.

So what is really causing these rocks to move across this usually dry lake bed? Death Valley National Park shares the following:

What powerful force could be moving them? Researchers have investigated this question since the 1940s, but no one has ever seen the process in action –until now.

In a new paper published in the August 27, PLOS ONE, a team led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego, paleobiologist Richard Norris report on first-hand observations of the phenomenon. Because the stones can sit for a decade or more without moving, the researchers did not originally expect to see motion in person. Instead, they decided to monitor the rocks remotely by installing a high-resolution weather station capable of measuring gusts to 1 second intervals and fitting 15 rocks with custom-built, motion-activated GPS units. (The Park Service could not let them use native rocks, so they brought in similar rocks from an outside source.) The experiment was set up in Winter 2011 with permission of the National Park Service. Then –in what Ralph Lorenz of the Applied Physics Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins University, one of the paper’s authors, suspected would be “the most boring experiment ever” –they waited for something to happen.

But in December 2013, Norris and co-author James Norris (of Interwoof and Richard’s cousin) arrived in Death Valley to discover that the playa was covered with a shallow pond no more than seven centimeters (three inches) deep. Shortly after, the rocks began moving.

“Science sometimes has an element of luck,” Richard Norris said. “We expected to wait five or ten years without anything moving, but only two years into the project, we just happened to be there at the right time to see it happen in person.”

Their observations show that moving the rocks requires a rare combination of events. First, the playa fills with water, which must be deep enough to allow formation of floating ice during cold winter nights but shallow enough to expose the rocks. As nighttime temperatures plummet, the pond freezes to form sheets of “windowpane” ice, which must be thin enough to move freely but thick enough to maintain strength. On sunny days, the ice begins to melt and break up into large floating panels, which light winds drive across the playa pool. The ice sheets shove rocks in front of them and the moving stones leave trails in the soft mud bed below the pool surface.

“On December 21st, 2013, ice breakup happened just before noon, with popping and cracking sounds coming from all over the frozen pond surface”, said Richard Norris. “I said to Jim, ‘This is it!'”

These observations were surprising in light of previous models, which had proposed hurricane-force winds, dust devils, slick algal films, or thick sheets of ice as likely contributors to rock motion. Instead, rocks moved under light winds of about 3-5 meters per second (10 miles per hour) and were driven by ice less than 5 millimeters (0.25 inches) –too thin to grip large rocks and lift them off the playa, which several papers had proposed as a mechanism to reduce friction. Further, the rocks moved only a few inches per second (2-6 m/minute), a speed that is almost imperceptible at a distance and without stationary reference points. “It’s possible that tourists have actually seen this happening without realizing it,” said Jim Norris. “It is really tough to gauge that a rock is in motion if all the rocks around it are also moving”.

Individual rocks remained in motion for anywhere from a few seconds to 16 minutes. In one event, the researchers observed that rocks three football fields apart began moving simultaneously and traveled over 60 meters (200 feet) before stopping. Rocks often moved multiple times before reaching their final resting place. The researchers also observed rock-less trails formed by grounding ice panels –features that the Park Service had previously suspected were the result of tourists stealing rocks.

“The last suspected movement was in 2006, and so rocks may move only about one millionth of the time,” said Lorenz. “There is also evidence that the frequency of rock movement, which seems to require cold nights to form ice, may have declined since the 1970s due to climate change.”

Richard and Jim Norris, and co-author Jib Ray of Interwoof started studying the Racetrack’s moving rocks to solve the “public mystery’ and set up the “Slithering Stones Research Initiative” (“Science for the fun of it”) to engage a wide circle of friends in the effort. They needed the help to repeatedly visit the remote dry lake, quarry rocks for the GPS-instrumented stones, and design the custom-built instrumentation. Ralph Lorenz and Brian Jackson (of the Department of Physics, Boise State University), in contrast, started working on the phenomenon to study dust devils and other desert weather features that might have analogs to processes happening on other planets. “What is striking about prior research on the Racetrack is that almost everybody was doing the work not to gain fame or fortune, but because it is such a neat problem”, says Jim Norris.

So is the mystery of the sliding rocks finally solved?

“We documented five move events in the two and a half months the pond existed and some involved hundreds of rocks”, says Richard Norris, “So we have seen that even in Death Valley, famous for its heat, floating ice is a powerful force driving rock motion. But we have not seen the really big boys move out there….does that work the same way?”

We pulled up our ice chests for chairs, sat down and had our lunch.

We then explored. The surface of the playa is very fragile. Driving on it or anywhere off established roads is prohibited. We were cautioned to not move or remove any of the rocks. When the playa is wet, they want you to avoid walking in muddy areas and leaving ugly footprints. This prevents others from enjoying this unique area. Driving offroad is strictly prohibited.

I walked out to the edge of the Playa and the snow was melting before our eyes, leaving interesting patterns.

Gail and I walked around the south side of the Playa.

Beautiful reflections started to appear.

We realized that we were seeing that mystery of the moving rocks begin to develop before our eyes. We had a very rare opportunity to visit the Racetrack with fresh snow on it, see if melt and when it would freeze that night, would begin the process of moving those rocks with the help of some wind.

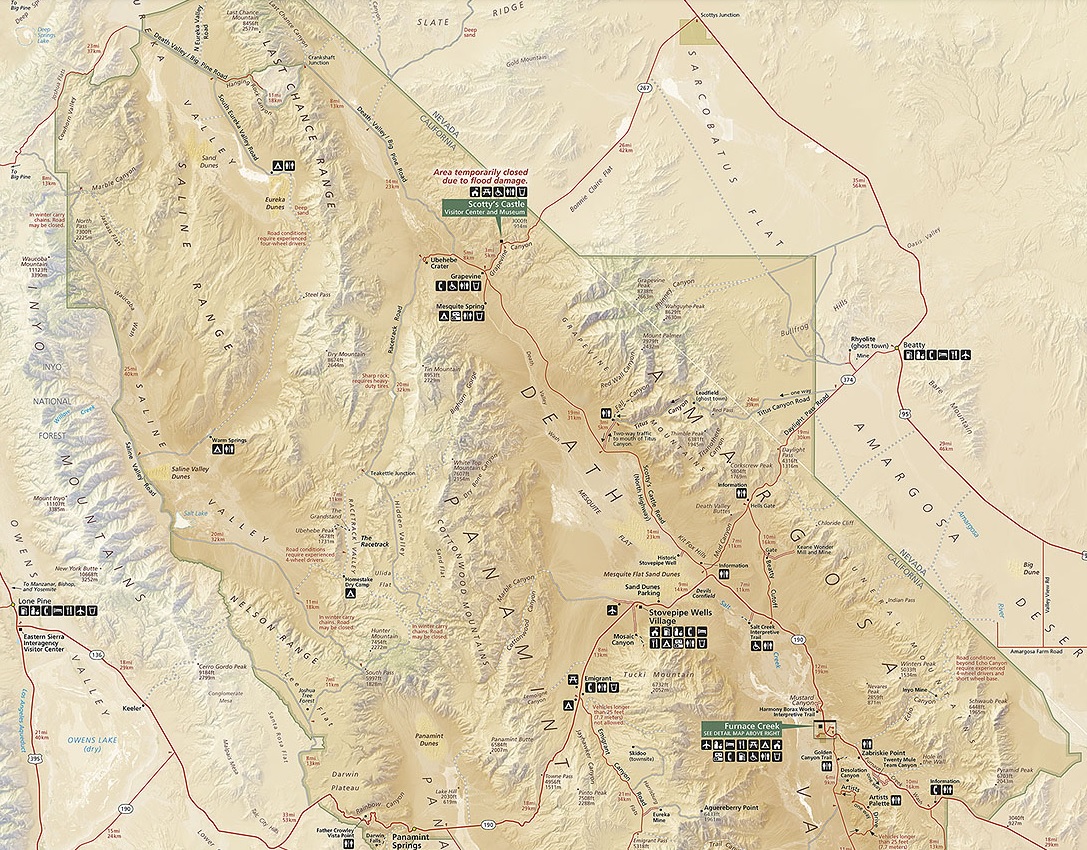

Map:

Sources:

Digonnet, Michel, Hiking Death Valley: A Guide to its Natural Wonders and Mining Past, Second Edition, March 2016

The Racetrack Death Valley National Park

Death Valley National Park Home Page

Death Valley National Park Hiking

Prior Blogs in this Area:

Escape to Death Valley: Salt Creek Pupfish March 19, 2017

Escape to Death Valley: Mesquite Sand Dunes March 5, 2017