We walked in the footsteps of the miners who had occupied this land back in the 1870’s and 1880’s on this hike, with misty clouds drifting in and out along the trail and views. Hiking up to the Ghost Town of Dana City located in the Tioga Pass is a whole different hike in different seasons and weather. I had snowshoed this route early this spring but on this day we were hiking in the clouds.

The predicted weather for the day was a high of about 70 degrees with possible thunderstorms in the afternoon so I wore shorts. The actual high was about 50 with 20-30 mph winds and we were in the clouds all day.

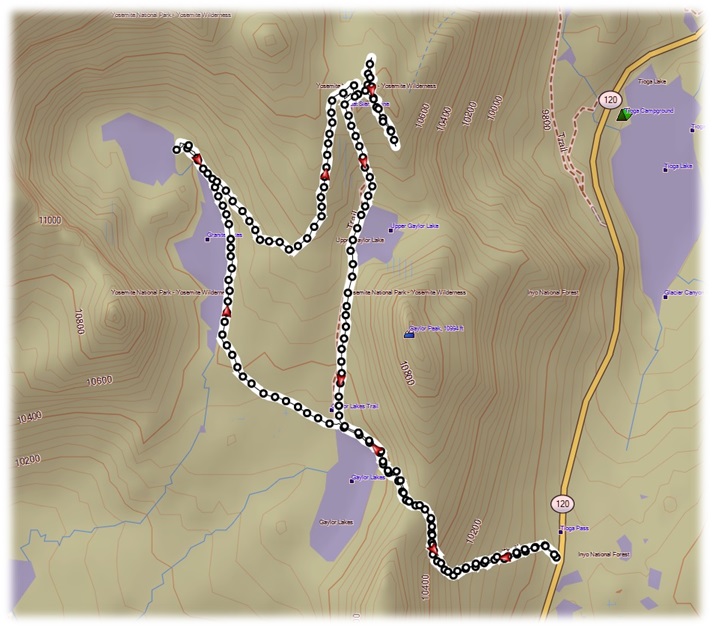

Where: Yosemite National Park

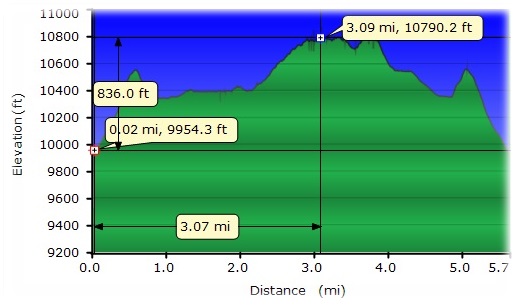

Distance: 5.64 Miles

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Range: 9.947′ – 10,804′

Date: August 5, 2014

Maps: Falls Ridge Quad

We drove to the parking lot at the Tioga Pass East Entrance to Yosemite and parked, utilized the nice clean restrooms and headed up the trail.

One of the reasons that I love hiking in this country is because of the rich mining history that occurred in these parts and when I am up here, I cannot stop thinking of the characters that braved this tough country to pursue their dreams of finding gold and silver. “The Great Silver Belt,” which runs from Tioga Hill to Bloody Canyon, was where the illusive minerals were that they were searching for. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent. Some mines paid off, a few people made some money, but most never produced. When I am hiking in this country, I wonder who these men and women were and what their lives were like. There were some real characters in these parts.

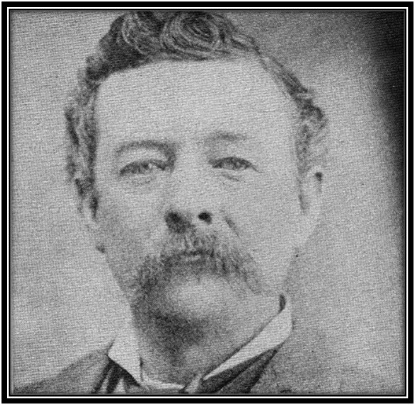

One of the sources that we can use to look back on the mining days of this area is through the local newspaper of the time at Lundy called the Homer Mining Index (HMI). I would like to introduce you to the editor of that newspaper because he is going to help tell the story today, a man by the name of James W.E. Townsend. Some say he was inspiration of Bret Harte’s “Truthful James,” the source of Mark Twain’s Jumping Frog story.

HMI, September 4, 1894: “It requires inventive genius to pick up local news here now. The scribe has to trust to his imagination for facts and to his memory for things which never occurred.”

Virginia Chronicle (Virginia City, Nevada), May 27, 1882: “James W. E. Townsend the gentleman who is making the local department of the Reno Gazette sparkle these days has led a remarkable life. From information imparted by him to his friends while he lived on the Comstock, we learn that he was born in Patagonia, his mother, a noble English lady, having been cast ashore after the wreck of her husband’s yacht, in which they were making a pleasure trip around the globe. She was the only person saved.

After the birth of her son, and September having arrived (there being an “r” in that month) she was killed and eaten. Jim was saved out as a small stake and was played until his twelfth year against the best grub at the command of the savage tribe for fattening purposes. Then he escaped on a log, which he paddled through the Straits of Magellan with his hands, and was picked up by a whaler and taken to New Bedford.

At the age of 18 he entered the Methodist ministry and preached with glorious results for ten years, when he went to the Sandwich Islands as a missionary to the Kanaka heathen, and remained for twenty years. Then he reformed and returned to New York and opened a saloon, which he ran successfully and made a large fortune.

In an evil hour for himself, but to the world’s advantage, he tried his hand at journalism. Fifteen years of this reduced him once more to poverty and preaching. For thirty years longer Mr. Townsend occupied the pulpit, when he went back to the saloon business, after eighteen years of industrious drinking on the part of the public he brought his wealth to the Pacific Coast. This was in 1849. For several years Mr. Townsend ran simultaneously eight saloons, five newspapers and an immense cattle ranch in various parts of the Golden State.

In 1859 the enterprising gentleman was suddenly afflicted with a disease which for many months compelled him to lie on his back in one position. This misfortune was, with the cruel levity of those rough days, turned to account by his acquaintances, who dubbed him “Lying Jim” Townsend, and ever since the sobriquet has stuck to him. For the last decade he has devoted himself to journalism and is, of course, once more poor. Some of his friends who are of a mathematical turn have ascertained from data furnished them by Mr. Townsend in various conversations the remarkable fact that he is 384 years old. Notwithstanding his great age, however, the gentleman still writes with the vigor of youth, and his shrewd humor is making for the Gazette more than a local reputation.”

It is a fact that he was known as Lying Jim Townsend and the Virginia Chronicle article was a very nice story but here is the reality. James Townsend was born August 4, 1836 in Portsmouth, Rockingham, New Hampshire to Ann Huntress and John R. Townsend. It appears that he was married three times, first to Elizabeth Lindsey, next to a woman named Belle, then to Sarah Jane McNulty. Researchers show that he died April 11, 1900 in Lake Forest, Michigan but I can’t figure out what he was doing there.

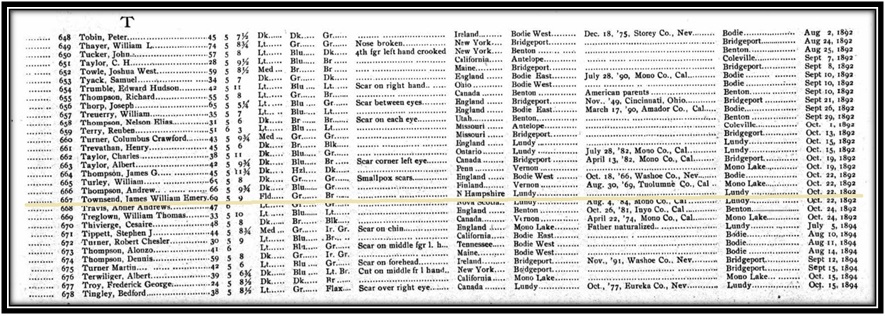

From 1888 till 1892, James Townsend was registered to vote in Lundy, Mono County. The last record that I find for him is from the 1892 California Voter Registration record below.

Lying Jim Townsend was a man of many more talents than just his role of editor. He also invented a rock crusher and was working on a flying machine, long before the Wright Brothers made their famous first flight.

HMI, October 2, 1880: “The arrastra is constructed on the most scientific methods, illustrating Jim’s aptitude for mechanics, which is only excelled by his capacity for whiskey, which is simply unlimited.”

As we hiked along Middle Gaylor Lake up to the Granite Lakes, the mist would float in and out. It certainly put me in the mood to think about the people who were in this neck of the woods before us. If you look close enough, you can make out the remnants of old roads that were utilized back in the mining days.

Although the day was gray, pops of color were provided by the wildflowers. I even came across a young mushroom that was popping its way up through the ground. The beautiful pattern on the top was a work of art.

When we arrived at the upper of the Granite Lakes, we saw some people out in the lake in a pack raft. Since it was cold and cloudy and we couldn’t see too much, we decided to head toward Dana City and have our lunch up there. Cross country we went!

There was an old mining area referred to as Tioga Hill, located about one mile northwest of Tioga Pass on the eastern boundary of Yosemite National Park. A band of white quartz runs along its crest and is known as “The Great Silver Belt.” This is the setting for the mining boom in the 1870s and 1880s that occurred in the area of Dana City. Here is one story from the 1958 book “Ghost Mines of Yosemite” by Douglass Hubbard about how the area got its mining start.

“There are several tales told about the discovery of The Sheepherder, most famous of these lodes. One goes like this: Early in 1860 Michael Magee, justice of the peace at Big Oak Flat during flush times in that camp, Captain A. S. Crocker, of Crocker’s Station, L. A. Brown, a surveyor, “Doc” George W. Chase, a dentist, and Professor Joshua E. Clayton of Mariposa were prospecting in the vicinity of Bloody Canyon. They camped near Tioga Pass to rest their animals and to look around. Clayton and Chase had been to the Mono Diggings the year before, and in returning home Chase crossed Tioga Hill and discovered the Sheepherder Lode.

“He may have been the first human to see its immense proportions. He kept mum about his discovery except perhaps to Clayton, who assayed his ore. While the 1860 party was camped at Lake Jessie (called Tioga Lake today) at the eastern base of Tioga Hill, Doc Chase remarked that if they could spend one day more there, he would locate and claim “the biggest silver ledge ever discovered”. Next day, while the others remained in camp, Chase, armed with a pick and shovel and a small tin can, struck out northward at daylight and ascended Tioga Hill by about the same course as the trail which now leads from the Great Sierra tunnel to the old works of the company on the hill.

“Reaching the Sheepherder Lode where it crosses a shallow ravine under a small lake, Chase unsoldered the can, straightened it out, and on the inner side scratched out his location notice with his knife. This he placed between two rocks on the massive croppings. Carrying as much ore as he could, he returned to camp. Next morning the party separated; Magee and Crocker returned to their homes, while Brown, Chase and Clayton swung around by Bloody Canyon to Monoville, where Clayton had his assaying outfit. Had they crossed Mount Warren Divide and come down Lake Canyon they may well have discovered the rich croppings which later became the May Lundy Mine.

“At Monoville they were to test the Tioga ore and Clayton was to devise a plan for a smelting furnace. But simultaneously with their arrival at Monoville there came in some men who had struck rich rock at what later became Aurora, Nevada. They had come over to get Clayton to make some assays. These ran so high that forgetting “the biggest silver ledge ever discovered” Clayton packed up his assaying outfit and the three started for Aurora. All made money as they followed new strikes. None returned, yet they never ceased telling their mining friends about the “thundering big silver ledge” on Tioga Hill.

“The news of a big silver ledge at the summit of the Sierra spread through Tuolumne and Mariposa counties in a short time, but soon passed into tradition amidst the excitement incident to the opening of the rich mines at Virginia City and Aurora. In 1874, as the story goes, 14 years after Chase’s discovery, the Sheepherder Lode was rediscovered by William Brusky, Jr., a boy from Sonora, Tuolumne County, who was tending a large band of sheep on Tioga Hill for his father. A rusty pick and broken shovel and the tin notice of location were found just as Dr. Chase had left them, except that the shovel had been almost destroyed by rust, and the location notice was illegible except the words, “Notice, we the undersigned” and the date 1860.

“Young Brusky had heard of the tradition and had been keeping on eye open for the ledge. Elated as he was when he made his discovery, he was disappointed when he returned home with samples of the ore. This his father pulverized in a mortar, panned, and pronounced worthless. The following summer, 1875, Brusky sank a small hole in the ledge and procured some better-looking ore. But still no one in Sonora would take any interest in it until the winter of 1877 when someone assayed the rock and found it to be rich in silver. Then everyone wanted to be in on the find.

“In 1878 Brusky again returned to Tioga Hill and on the second day of August located four claims of 1500 feet each along the Sheep herder Lode, naming them the Tiptop, Lake Sonora, and Summit. All of them were subsequently purchased by the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Company. Young Brusky committed suicide on August 28, 1881.

“Paralleling the Sheepherder Lode some 800 feet to the south is the ledge known as The Great Sierra. Among its mining claims are the Bevan, Ah Waga, Hancock, Atherton, and the High Rock. Perhaps the most important of these is the latter, site of the old village of Dana. Located originally by W. W. Rockfellow in October 1878 as the High Rock, it was later called the Mount Dana and finally the Great Sierra. Here, amidst unrivalled Sierran grandeur, stands a beautiful old stone cabin. Constructed of loose slate by an unknown craftsman, it is a masterpiece of dry-rock masonry. Its dirt-filled walls and heavy hand-made wooden door provided protection for many a miner when biting winds whistled across Tioga Hill.A few yards to the north of the cabin are other buildings, now in ruins, nestled around two shafts—on inclined prospect shaft or the white mother lode, and a double compartment shaft which had been sunk 100 feet when summit work was abandoned.”

One of my hiking buddies, Rick, is a geology buff and we always learn something related to this when we hike with him. He took a closer look at rocks in the area, even finding a stash of crystalline rock, thanks to a helpful marmot’s hole that uncovered it.

What was it like to live at this area called Dana City? The old mining communities of Lundy, Bennettville and Dana City were closely knit. Dana City received a post office in 1880 and is said to have had up to 1,000 people living in it at heyday. Now, let’s let the Editor of the Lundy newspaper Homer Mining Index (HMI), James W. E. “Lying” Townsend, take over the story telling.

HMI, November 12, 1881: “The wind was so terrific on Tioga Hill Wednesday night that it burst in the doors of buildings, and would have doubtless carried away the shaft house at the Great Sierra Mine but for the support given the buildings by the substantial gallows frame of the hoisting works.”

HMI, November 26, 1881: “A post office has been created on Tioga Hill, to be known officially as Dana, and Frank W. Plains appointed postmaster; but Frank is down in Yosemite Valley for the winter and the emoluments of the office ($12.25 a year) don’t appear to be sufficiently attractive to induce him to climb 27 miles up the mountain on snowshoes to qualify.”

There was a lot of excitement about the various claims in this area and some say that “claims were changing hands like cards in a poker game.” Shortly before his untimely death, Brusky and several of the Sonora friends who owned the adjoining claims on the Sheepherder Lode attempted to incorporate as The Consolidated Lake, Summit and Sonora Claims, while the High Rock was transferred to the Mount Dana Mining Company and then to the Great Sierra Mining Company, both California corporations. Not much is known of the operations of the Great Sierra Mining Company, predecessor of the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Company. It had good buildings, a good supply of food and other essentials. We get some glimpses of that time through the Homer Mining Index.

HMI, November 19, 1881: “A frightful accident occurred at the Great Sierra Mine, Tioga District, about 11 a.m. on Thursday last, by which three men were seriously, one probably fatally injured. It is the old, old story of thawing frozen nitroglycerine powder on a stove. A short distance east of the shaft and not far from the blacksmith anvil stood a large box stove, which was usually kept glowing with heat. In, on, or about this stove someone placed six sticks or cartridges of frozen Excelsior powder, for the purpose of thawing it out for use in the crosscut on the 100 foot level as the day shift came up for dinner. . . . While James H. Kickham of Lundy, the company carpenter, was near the stove, the blacksmith was further off and near the anvil, and George M. Lee was still further away in a corner of the blacksmith shop near the forge, the powder exploded with a terrific crash, tearing away the outer wall of the blacksmith shop and knocking the men senseless. Kickham was severely and probably fatally injured, receiving a ghastly wound on the head, several lacerations of the arm and body, and being literally torn to pieces about the pelvic region. The blacksmith was also severely injured, receiving several cuts and bruises about the head and body, and possibly some internal injuries.

“George M. Lee was at first thought to have escaped injury further than temporary shock from the concussion, but when our informant left, 15 minutes after the explosion, Lee was suffering great internal pain. Charlie Benson was dispatched to Lundy for medical aid, making the trip in four and a half hours, on foot without snowshoes, and most of the distance (about 11 miles) through snow waist deep. On his arrival, a dispatch was sent to J. C. Kemp, resident manager of the Great Sierra Company, who was in Bodie at the time. That gentleman at once engaged Dr. D. Walker to go to Tioga to attend the wounded. It was found impossible to obtain a team, however, until 2 o’clock the next morning, at which hour Mr. Kemp left Bodie and drove Dr. Walker to Lundy, arriving here at daylight. Early yesterday morning Moreno’s caravan of pack mules, unloaded, was dispatched to Tioga to break a trail through the snow, and Dr. Walker . . . followed soon afterward.”

HMI, November 26, 1881: “At last account James H. Kickham, George M. Lee, and Benjamin Martin, the three men injured by the powder explosion at the Great Sierra Mine last week are doing well, and all of them are recovering rapidly. George M. Lee is able to be around as usual, but cannot be induced to sit down, even when engaged with writing. (The fragments of the demolished stove struck George in the rear, below the belt, and numerously.)

“Kickham received between 150 and 200 wounds from the fragments of the stove and a large tin can that sat on top of it, and is scarified on the left side from the crown of his head to the sole of his foot. . . . A piece of the tin can, rolled into a solid projectile was driven into Martin’s skull about two inches above the eye, and was pulled out by Dr. Walker by main strength; but, strange to say, the skull was not broken. A mule, standing near the building at the time of the explosion, had a large hole torn in his breast. Dr. Walker reached the scene of the accident on the evening following its occurrence, after a most fatiguing climb of more than a mile up the steep mountain, up to his neck in soft, fresh snow and in the dark and immediately proceeded to dress all of the wounds, including that of the mule, for the doctor is as good on mules as he is on men.”

HMI, December 2, 1881: Upon this sled-stretcher Kickham was placed at daylight Monday morning, and the volunteers started with him for this place, Lundy, a distance of about 11 miles, involving ascent and descent aggregating fully 12,200 feet reaching here at dark the same evening with the wounded man feeling fresher and perhaps stronger than any one of the strong-limbed but now exhausted giants who had left the summit with him in the morning.

By May of 1882, the main shaft had been mined down through the granite to over 100 feet. At this time, management decided to change strategy and relocate to the hill above Bennettville and start a horizontal tunnel westward towards the Great Sierra Mine where the Sheepherder Lode was projected to be at. Dana was soon abandoned.

Tunnel work above Bennettville continued through the end of 1883 but the Great Sierra Consolidated Mining Company was having financial difficulties. There was big talk about the tunnel being very close to cutting into the Sheepherder Vein. On January 16, 1884, they appealed to shareholders that they were in debt $225,236.38, and that money would have to be provided to meet the expenses of continuing work on the mine. The news reports in the Homer Mining Index also attempted to generate interest in a pending Sheepherder Lode big strike.

HMI, July 12, 1884: As to the reported strike in the Great Sierra tunnel. . . . it will be well to await reliable information, as outsiders are not yet allowed to know anything about the importance of the strike. That the Sheepherder lode has been cut into is certain; but there is nothing surprising or exciting in that fact, as such a strike was inevitable. As we understand it, two series of shots were put into the solid quartz after it was reached, and no one but the foreman has been into the tunnel since the last series of blasts were exploded, and we doubt if even he has taken any steps to ascertain the value of the rock. To us the Sheepherder lode has been an open book ever since we first examined the outcrop, some years ago. . . . The temporary suspension of work in the tunnel has no significance of consequence to the public.

On July 3, 1884, the Executive Committee made the decision to suspend all operations.

HMI, July 12, 1884: “A party of Great Sierra miners, taking advantage of the temporary suspension of work in the tunnel, have gone over to Parker Lake to catch trout.”

As day after day went by and no word was received to return to work, the miners began straggling off to seek other employment, and Bennettville became deserted—a ghost city with only a couple of people storing property and greasing up the machinery at the tunnel.

Lawsuits were made with the worth decided at $277,083.86. A Sheriff’s sale Mono County in 1888 liquidated the properties, which were purchased by William C. N. Swift, Trustee, for $167,050. Heirs of Swift resumed work on the tunnel in 1933, pushing the length of the tunnel back several hundred feet but they never found that Sheepherder Vein. Work ceased in 1949 after the death of Antoinette Swift, then the property was disposed for back taxes

Mining records indicate that the mine produced Chalcopyrite, Cobaltite, Galena, Gold, Pyrite, Pyrrhotite, Quartz and Tetrahedrite, which contains Silver. I could not locate any production values.

Walking through the old buildings and hints of old roads in Dana City can help you get some glimpses of this ghost town and mining area that once thrived in the Lundy, Bennettville and Dana City area.

It is hard to believe that some of these old timbers are over 100 years old. There were many open mines that you needed to be careful around and not get too close to. So I leaned over and snapped a few pictures of them.

We did a bit of exploring that day, checking out the remains of the old buildings. I ended up putting on my rain pants at lunch because those shorts that I started with just weren’t cutting it.

I believe this is what remains of the Powder Room.

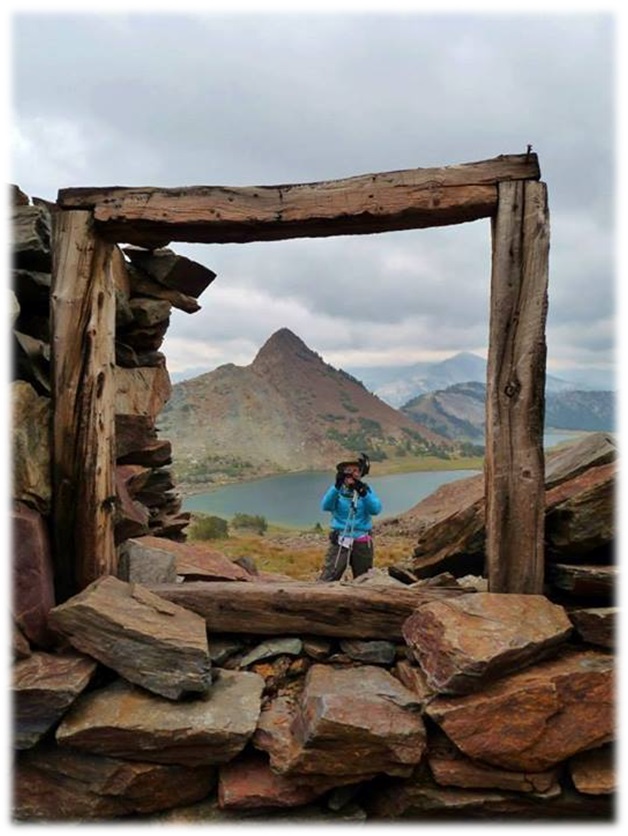

I really like this picture that I took of Debra Sutherland as she was taking a picture through the old window in the old miner’s rock cabin. And the next picture is what she was taking a picture of. . .me!

Deb took this picture as we headed back down the trail toward Gaylor Lakes.

Our adventure wasn’t over yet though. As we topped over Gaylor Ridge, we ran into a National Park Service employee and her crew. They were the ones that we had seen in the pack raft at Upper Granite Lake. She shared with us that they were taking water samples up there and after we asked her what she discovers in those water samples, she shared that they find pollution from the valley all the way up here. That is so sad. (Next two pictures by Debra Sutherland)

We headed down the hill with Dana Meadows in front of us and that gorgeous view. What a wonderful day!

Sources:

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Tioga_Road_%28HAER_No._CA-149%29_written_historical_and_descriptive_data

Day Hikes in the Tioga Pass Region, John Carroll O’Neill & Elizabeth Stone O’Neill, 2002

Hubbard, D. H.,Ghost Mines of Yosemite, 1958, Awani Press, Fresno.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lying_Jim_Townsend

Russell, C. P., Early Mining Excitements East of Yosemite, 1928, SCB, 13(1):40-53

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/ghost_mines/discovery.html

Homer Mining Index

http://www.lundycanyon.com/the-homer-mining-index/

The Virginia Chronicle (Virginia City, Nevada), May 27, 1882

California State Library, California History Section; Great Registers, 1866-1898; Collection Number: 4 – 2A; CSL Roll Number: 27; FHL Roll Number: 976939.

http://www.rockcreeklake.com/board/index.php?topic=359.0

http://www.mindat.org/loc-83377.html

Prior Blogs on This Area:

https://sierranewsonline.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=3636:gaylor-granite-lakes-snowshoe-hike&Itemid=535

https://sierranewsonline.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=1178:gaylor-lakes-great-sierra-mine-hike-part-1&Itemid=535

https://sierranewsonline.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=1207:gaylor-lakes-great-sierra-mine-hike-part-2&Itemid=535