OAKHURST — Fire steals, even from those who fight it. It robs creatures of habitat, takes possessions, property, land, and sometimes, life.

Fire also gives back: flames can be restorative, over time, for overgrown forests filled with beetle-infested, drought-plagued timber. Fire makes way for fledgling trees and new families of fauna to thrive on once-sterile ground. And fire can remind us to cherish what we have now.

Of the 17 structures burned in the course of the Railroad Fire, 5 were historically significant buildings managed by the U.S. Forest Service, Sierra National Forest at Westfall Ranger Station. While initial reports indicated that all the Forest Service buildings survived, subsequent inspections by damage assessment teams proved otherwise.

Click on images to enlarge.

It was a hot Tuesday afternoon at the end of August, when fire was first reported near the Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine Railroad in Fish Camp. Ultimately, the Railroad Fire burned over 12,000 acres, tearing through tinder-dry fuel, most of it on the Sierra National Forest. As it progressed, despite best efforts, the flames prompted evacuations, fear and uncertainty.

The Railroad Fire burned for more than two weeks before it was contained. In the end, while six firefighters were injured, there was no loss of human life on the fire. However, in the case of a handful of buildings, fire stole nothing less than history.

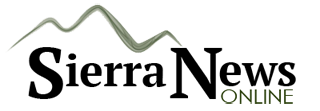

Miami Field Base on hill behind Westfall Ranger Station Engine Bay, ca. 1930, courtesy Terry Munhall (USFS photo HP03595)

Part of a small compound located just south of the ignition point, five of the lost structures were known collectively as the Miami Field Base at today’s Westfall Ranger Station. The Westfall Ranger Station (then known as Miami Ranger Station) was first established there in the late 1920s, and the Bureau of Entomology established the field base there in 1937-38. Both units of the Federal Government, they co-existed while the field base was in operation. The Miami Field Base site included a rustic log garage, a field based residence, a garage/workshop, a storage building, a concrete foundation where once stood an insectary – a place for breeding insects to be studied in field research – and an office (and sometimes insectary) referred to as the “bug lab.”

Located up on a hill behind the old railroad grade, unseen from the highway, these buildings were historically significant; in part for their Depression Era architecture and construction technique. They’re especially interesting in light of the scientific work conducted inside some of the buildings — including the “bug lab.”

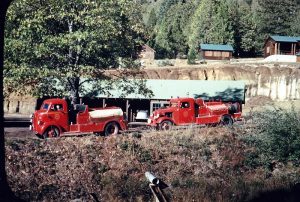

The property is currently a Forest Service Fire Station, and home of the Westfall engine, named for one of the first rangers in the area, Eldridge Westfall.

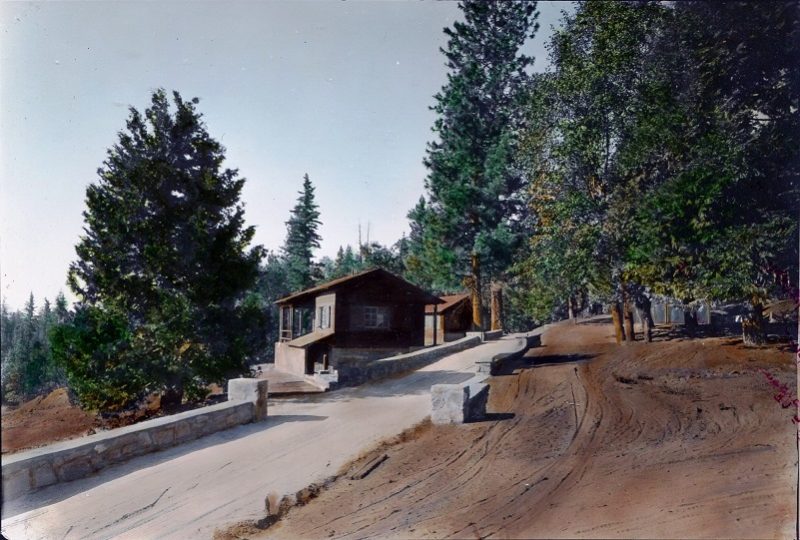

Miami/Westfall: CCC constructed retaining wall and walkway remain after Railroad Fire, photo courtesy Erin Potter, USFS, Sierra National Forest

Eighty years after being built as a center of study for ways to compete with tree-killing beetles during a then-unprecedented infestation in the western forests, the compound would burn to the ground in the Railroad Fire, and the bugs and drought would win this round.

Erin Potter is the Bass Lake District Archeologist for the Sierra National Forest, working out of the North Fork office. Her primary responsibility is to make sure the Forest is in compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act and other laws pertaining to cultural resources, including anything 50 years old or older.

“It’s a really unfortunate thing,” says Potter. “The field base was a regionally significant gem on our forest. The construction was beautiful and unique, and we are so sad it’s gone.”

She emphasizes that no firefighter ever wants to see property destroyed, including their own.

“They are trained to protect, and will try to save even the smallest items on your property if they can,” Potter says. “When they can’t get to a structure in time to save it, if fire activity is erratic, fast and dangerous, they are tremendously saddened by the loss of property just as citizens are. It’s frustrating to make a stand to defend property and being unable to. Being on the district, it’s close to their hearts.”

Historic Evaluation and Determination of Significance

A study was conducted in 1998, prompted by the need for repairs and improvement to the water system on site, and a mandate to document Forest Service property with potential historical significance. The specifics of the structures were documented for the Sierra National Forest in a “Historic Evaluation and Determination of Significance for the Miami Field Base/Westfall Ranger Station,” by Thomas E. Nave. The document provides extensive history and background on the property.

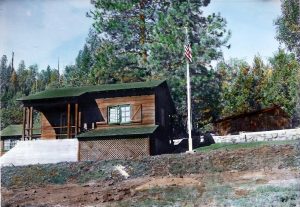

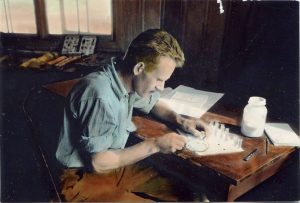

Researcher inside Miami Field Base Office ca. 1930-1940, courtesy Sierra National Forest (USFS HP04313)

By 1937, according to Nave, it was clear to the Forest Service that they had a beetle problem like nothing ever seen before. Realizing the economic impact of the beetles on forestry – amounting to the loss of several billion board feet of timber – the California Chamber of Commerce sparked a move to provide bark beetle research facilities.

Laboratory field bases were designed from which to study bark beetles. Because there were differences in the infestations between trees on the east side versus the west side of the Sierra Nevada range, two locations were chosen for the labs — one on the Lassen National Forest and one on the Sierra National Forest.

Seven thousand dollars was set aside for the project, with each field base consisting of an office, laboratory, rearing facilities, a shop, a garage, and camp living facilities. The construction was accomplished during the fall, winter and spring of 1937-38.

Unique not only in their architectural design and overall purpose, the buildings were also significant because of the people who built them. Working under the supervision of Forest Service personnel, labor for the months-long project was provided by Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) personnel from the North Fork CCC camp, as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Improvement of the grounds, including concrete and rock walls, was completed in the summer of 1938 by Emergency Conservation Work crews from a camp near Yosemite Forks.

After the Railroad fire, it’s those retaining walls that remain – a tarnished monument to the men who built them as the country struggled to overcome the Great Depression.

The Field Base Office

According to Nave, the Miami Laboratory served as a base for the study of west side bark beetle problems: mountain pine beetle, western pine beetle, 5-spined Ips, fir engraver, and pine reproduction weevil.

Problems with native forest insects species becoming suddenly active after long periods of dormancy were investigated and evaluated. Severe infestations studied at the Miami laboratory included the pine reproduction weevil, ponderosa pine tip moth, lodgepole needle miner, Jeffrey pine needle miner, white fir sawfly and great basin tent caterpillar.

Between 1938 and 1944 the research work was centered on the mountain pine beetle, with the contributions on biology, predator controls, and characteristics of trees attacked. Through 1953 this base served mainly in the development of improved applied control techniques and methods, using chemicals that kill the bark beetles by contact and fumigation. — Nave

Among the reasons the place was deemed historically significant was the Depression Era architecture, seen in some of the CCC-built structures, such as the Field Base Office. Its use of native wood siding, native stone for retaining wall and steps, and landscape design in harmony with native plants are good examples of timeless architecture.

The designs, Nave noted, featured horizontal facades with v-groove siding, multi-paned windows, inset porches, moderately pitched roofs, and exposed rafter tails.

“It was a unique place in forest and regional history,” says Potter, referring to the Field Office they affectionately called the “bug lab.”

The whole area was a time capsule of that 1930s and 40s era, she says.

“It was like a little museum. Chairs, desks, beakers, prints of trees and bugs that they were studying and they used — and that’s all gone. It’s a heartbreaker.”

While the station is eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, it had not been nominated and listed on the National Register.

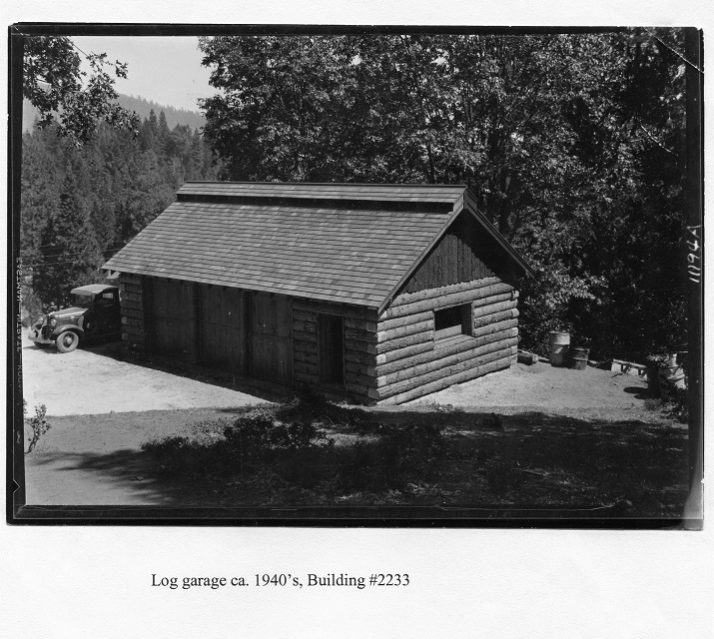

The Log Garage

Of interest today, and lost to the fire, is a rustic log garage completed in 1938. The building was constructed of experimentally treated logs, injected with chemicals including separate solutions of copper sulphate, sodium arsenite and zinc chloride.

Desperate to find some method to guard against repeated invasion by unwanted insects, the Forest Service experimented with ways to control the bark beetles, borers and fungi.

Nave believed that the rustic log garage was the most unique structure on the site. The chemicals were injected before the trees were felled. Ponderosa pine, sugar pine, incense cedar and while fir were injected and later, each log and its location in the structure was carefully recorded.

The rustic character of logs was preserved by nailing the bark. These logs remained soundly preserved against rot and insect damage for almost 40 years. They remain fairly sound to this day, with little rot present. — Nave

The logs remained pretty much intact up to the Railroad Fire, says Potter.

“There was some peeling of the bark and some log decay on the sill logs and the bottom of the structure, but for the most part, it appeared to be quite sound.”

The Insectary

The Insectary on the grounds was a seasonal structure and only the concrete foundation was permanent. The walls were housed in the log garage and burned along with it. During field base operations, it had been the on-site breeding locale for a host of pests under study by the researchers.

The Field Base Residence and Storage Building

Two structures that did not fit in with the Depression Era construction, and whose origins were undocumented, were the Field Base Residence and Storage Building.

The residence is a gabled front, board and batten structure with a moderately pitched, shake roof. Attached to the rear of this structure is a wooden tent platform that serves as a summer sleeping porch. The origin of the residence is unknown, but it is shown on the official plans for the field base. Its close association with the administrative site as a whole is a key. The storage building also appears on the 1930s plan for the station. It is a side-gabled, rectangular structure with a moderately pitched shake roof. This structure is built of vertical board walls, without battens, and sits on log piers.

The Field Base Residence and storage buildings are other unique features of the site that should be contributing elements. They are in their original location and are almost completely original. A visitor to the site in the late 1930s would instantly recognize them today. — Nave

The loss of the Miami Field Base complex to the Railroad Fire is one that will reverberate over time, throughout history. Early discussions were taking place to explore turning the location into an overnight living history rental to the public. Those who trod the CCC-constructed, rock-lined steps of the Miami Westfall site will now walk among ghosts.

“A lot of people grew up knowing it in the time when it was an active place, and have that connection,” says Erin Potter. “It’s tragic how this is, once again, an unprecedented time of tree mortality, because it was set up for that very reason – to study how we were going to address the beetle epidemic then.”

One piece of good news: while the Miami Field Base is gone, the Westfall Ranger Station is still NRHP eligible as a historic property. Fire steals, but it also gives a reminder of how important it is to preserve the past and present for the future.