YOSEMITE – Wildfire is part of life in the Central Sierra, and the sight of billowing smoke engenders fear in those who live in the Wildland Urban Interface.

But it is also an important part of the ecology, as is evidenced by the decades of study in Yosemite National Park. Officials are eager to witness the rebirth and renewal in the Empire Fire area with the coming of spring.

When the public hears that a wildfire is being allowed to burn in the park, they may mistakenly believe that the fire is just running rampant, with no management.

“The common misconception about Yosemite using fire on the landscape, is that we just let it go,” says Yosemite Fire Chief Kelly Martin. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

When lightning-caused fires are discovered in Yosemite, they are assessed for many things, including any threat to populated areas and the benefits to the ecosystem.

Martin says Yosemite is at the epicenter of managing wildfires for both ecological and protection objectives, and has a long history of using lightning fires to reduce fuels, thin the forest, and create a resilient ecosystem. This is a critical management component considering the decades of misguided fire suppression in the Sierra.

Before fire season begins, Martin and the Fire Management Committee discuss opportunities for where they’re going to allow fires to burn during the summer.

“One of the first things we look at is seasonality – how dry is it this summer? If it’s very dry, such as during a drought year, we will consider higher elevation fires. It’s cooler and wetter there, the trees are more broadly spaced, and not nearly as flammable as those in the lower elevations.”

They then look at the fire history in the area – are there burn scars in recent years? Can those patchwork burns be used to manage the fire? Is the fire beneficial for Yosemite?

They also consider fuel loads, and access for firefighters and their safety.

Fire used to be a natural part of the ecology of the forests of the Sierra, but for nearly 100 years, fires have been suppressed, leading to overgrown, sterile stands of timber, and heavy fuel loads on the forest floor. In Yosemite – to as large a degree as possible – they’re using fire the way it naturally occurs.

Fire used to be a natural part of the ecology of the forests of the Sierra, but for nearly 100 years, fires have been suppressed, leading to overgrown, sterile stands of timber, and heavy fuel loads on the forest floor. In Yosemite – to as large a degree as possible – they’re using fire the way it naturally occurs.

“Fire is one of the main tools we use to create healthy forests,” says Martin. “We’ve been doing this for almost 50 years, and it’s very important for the millions of visitors we serve. It’s also an opportunity to use fire in a beneficial way. Not all fire is bad.”

Martin says that most wildfires are not entirely devastating.

“Absolutely not every fire is bad, and we really want the public to understand that there are a wide variety of effects that we are going to see on the landscape. Like a campfire, wildfires can be small, or large. There are some that are hugely destructive and can destroy homes and threaten lives. But when fire is slow-moving, it provides more of an opportunity for us to allow it to play its natural role.”

In the lower elevations of the park where there are communities and more of a threat to life and property, fire continues to be suppressed, but other actions are being taken, such as thinning and removing downed fuels, and prescribed burning in the off-season.

“The intent of those investments today is that when a large wildfire hits those fuel breaks, it won’t destroy homes and property,” says Martin. “There’s no guarantee by any means, but doing preventative work in and around communities is important. The more we can actually have good fire on the landscape, the more it acts as a buffer and absorbs the energy from the more intense wildfire because you’ve removed a lot of the fuel.”

Martin says to goal is to protect the big trees, while reducing the number of smaller trees underneath the forest canopy, so that when wildfire enters that fuel treatment area, it drops to the ground, and there’s a better chance of taking suppression action and saving those communities.

In the higher elevations, fire managers have a wider range of options. As a part of any list of objectives on a wildfire, managers work to “keep costs commensurate with values at risk.”

On the South Fork Fire near Wawona, there were a lot of values at risk.

“We had two primary objectives; keep the fire north of the South Fork of the Merced River, and keep it from going further west into Wawona,” says Martin. “The fire was going deeper into the wilderness on the north and east, and we had to determine that it was not worth the money or the danger to firefighters to suppress that part of the fire. We made a deliberate decision to let the fire burn into the wilderness where there’s nothing to save in terms of life and property.”

Fire managers assessed the changes in fuel types and the natural barriers, and worked to steer the South Fork Fire into the higher elevations where it would eventually burn itself out — or as in this case, be stopped by the coming of snow to the high country.

Fire managers assessed the changes in fuel types and the natural barriers, and worked to steer the South Fork Fire into the higher elevations where it would eventually burn itself out — or as in this case, be stopped by the coming of snow to the high country.

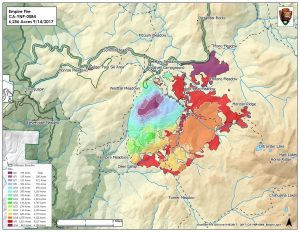

On the Empire Fire, which has burned over 6,300 acres south of Glacier Point Road, crews have been out in the burn area for about eight weeks, working different parts of the fire, reporting back to Martin such things as where they think the fire might cross the road, threaten property, or show more aggressive fire behavior.

“They’re scouting that so we can make decisions about letting it burn through an area that’s really heavy in fuel, in an effort to let it burn into an area that’s not so densely vegetated.”

Values at risk on the Empire Fire include the Bridalveil Campground, Yosemite West, and the Yosemite Ski and Snowboard area.

“We want to protect those areas and the Glacier Point Road and Highway 41 corridors, keep the fire where we can effectively manage it, and keep it moving off into the wilderness,” says Martin. “We can also use Hot Shot crews to conduct firing operations.

“We want to protect those areas and the Glacier Point Road and Highway 41 corridors, keep the fire where we can effectively manage it, and keep it moving off into the wilderness,” says Martin. “We can also use Hot Shot crews to conduct firing operations.

“Where you want the fire to stop may not be the safest place to put firefighters, so we look at natural barriers such as creek bottoms, areas of granite and fuel type changes. We then let the fire burn into these natural barriers. All this is not without a lot of effort and planning.”

Another benefit of allowing fire to burn and reduce the amount of small trees and brush, is more water.

Kristen Shive, Yosemite’s Fire Ecologist, says they have been studying the Illilouette Basin since 1974 when they began allowing fires to burn through that area.

“Yosemite is unique in that it is one of the few places in the west that, in the 70s, started doing controlled burns and allowing some lightning fires to burn for resource benefit; and most of that started in the Illilouette Basin.

“There’s an increased water yield coming out of that basin, because there are fewer trees sucking water out of the ground in these healthy, restored ecosystems. In a time of drought, we also found that there is less extensive tree mortality in Illilouette compared with other basins that are similarly situated.”

Before European-Americans came and started suppressing fire, these areas burned quite frequently, says Shive, probably every 5 to 15 years in the lower elevations, and every 20 to 30 years up higher.

Studying fire intensively over the last half-century has taught park officials a lot about the plants and animals that are adapted to ecosystems maintained by fire.

“The cones of the giant sequoias don’t open without fire,” says Shive. “There are some species of birds that will only use the openings created by fire. We are seeing a more diverse group of species in the basin, including a higher diversion of pollinator species, of bee pollinator species, of animal and plant diversity — we have a whole slate of species that are adapted to these different stages, all of which are maintained by fire.”

The lack of fire has had a dramatic effect on ecosystems as well as how fires burn today. Shive says that decades of allowing fires to burn in Illilouette has shown that suppression has not only blocked the benefits of fire, but has led to larger, more intense wildfires.

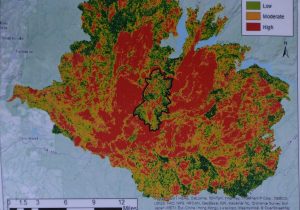

In the 2013 Rim Fire, that scorched over 257,000 acres on the Stanislaus National Forest and in Yosemite, the fire severity map shows just how destructive intense fires can be.

In the 2013 Rim Fire, that scorched over 257,000 acres on the Stanislaus National Forest and in Yosemite, the fire severity map shows just how destructive intense fires can be.

“When a fire burns small patches of trees, that isn’t necessarily a bad thing,” says Shive. “But when you get an area that’s over 5,000 acres in which more than 90 percent of the vegetation is destroyed, that brings really dramatic changes to the ecosystem. That’s total stand replacement; and because the trees only seed so far from their parent tree – and you have no live trees in an area – that’s not going to be a forest again for a very long time.”

One tool Yosemite fire managers use to reduce fuel loads, restore forest structure, and thereby reduce the intensity with which wildfires burn — is prescribed fire. Crews go out and put fire down on the ground, but do it under controlled conditions.

“That’s the primary tool we use at the lower elevations,” says Shive. “We do that in the late fall or early spring when temperatures are lower and humidities higher. Fire doesn’t burn as hot or as severe, and that’s what we want — for fire to just go through and clean it up. We’re setting the landscape up so it can handle a fire in the middle of the summer when things are really hot and dry.”

“That’s the primary tool we use at the lower elevations,” says Shive. “We do that in the late fall or early spring when temperatures are lower and humidities higher. Fire doesn’t burn as hot or as severe, and that’s what we want — for fire to just go through and clean it up. We’re setting the landscape up so it can handle a fire in the middle of the summer when things are really hot and dry.”

Shive says that opening up the forest by taking some of the small trees and brush out, allows more sunlight to reach the forest floor.

“A dense forest is very shady, and lots of things can’t grow. Also, by burning up litter and duff, you open up the soil. There are some species that will only germinate with totally bare soil. You also recycle nutrients that other species need to survive. There are some species – like a lot of the shrub species you see in the park – whose seeds are cued by fire.”

One of the big questions when discussing the issue of wildfires is the effect on air quality – both for residents and for visitors who come to see the iconic vistas in the park.

“It’s a very, very difficult issue,” says Chief Martin. “If you can image 100 years ago, smoke would have been ubiquitous in July and August and into September, but there wouldn’t have been as much. Because we’ve continued to suppress this natural event for years and years, we’re now caught in a really difficult dilemma wherein smoke is produced from the very large logs and trees, and the dense duff and litter on the forest floor. Somehow that has to be removed, and the only way to remove it is through fire.”

Martin says there are a lot of “high pressure” days, when it’s very difficult for the smoke to get into the higher atmosphere where it can be transported away.

“We do understand that smoke and air quality is a huge issue, and we work very closely with the California Air Resources Board and our local air pollution control districts to time those prescribed fire opportunities where there is dispersion, and smoke is transported away from sensitive areas.

“It’s not perfect; we know we’ll have really smoky days and we try to balance that, but in large wildfires, smoke is an inevitability.”

As to what the vision is for the next 25 years and the role of fire in Yosemite, Martin says it’s a long game with several moving parts, and everyone needs to start thinking about fire in terms of a mitigation, rather than just suppression.

“It’s all hands on deck when we have wildfires going on in the summer,” she says. “But for the rest of the year, there’s a tremendous opportunity for us as fire managers and the public to think about what community protection and living with fire means. Prescribed fire is a good tool, so how much smoke can we live with in the off-season? What are we willing to spend on thinning and mechanical treatments? Those are all really big questions we need to wrestle with going forward.

“Our population is increasing and moving into fire’s environment, and we have to accept a certain amount of responsibility. It will be a combination of using all our tools in the fall, winter and spring. I think the taxpayers and communities will see greatly enhanced benefits if we think about a mitigation industry rather than a suppression industry. That mitigation could occur three-quarters of the year, rather than trying to squeeze it all in during the summer.”

It’s a very big, complicated tapestry, says Martin, with no one good answer, but she is looking forward to continuing the outreach to the public about the benefits and effective ways to manage fire.

“We don’t just want to tell the devastation story, but also the renewal story and the adaptation story of how we can better live with and accept fire.”

Both Shive and Martin are very excited to get into the burn areas in the spring to see the new life and learn more about the rejuvenating effects of fire, and how critical it is to the health of Yosemite’s forests. Both want to dispel the notion that fire destroys the forest, and bring awareness to the important role it plays.

“Next year you are going to see things growing,” says Shive.