Written by Gina Clugston —

YOSEMITE — People are mad. They’re upset about the name changes in Yosemite, they’re writing angry letters to Delaware North and threatening boycotts of the Tenaya Lodge, a Delaware North property in Fish Camp. The resort’s several hundred employees don’t have a dog in this fight, but must suffer the very vocal condemnation of the outraged.

So, as people continue taking to social media to voice their indignation at what many deem “corporate greed,” this is, fundamentally, a contract dispute. The situation prompted a careful reading of recent court documents to understand the facts of just how the parties involved arrived at this impasse.

In 2015, Delaware North Companies Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Inc. (DNCY) lost its contract as the Yosemite Concession Services provider, to competitor Aramark, after 23 years in the Park; in part, claims DNCY, due to the actions of the National Park Service (NPS), U.S. Department of the Interior.

In a lawsuit filed in September 2015 in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, and an Amended Complaint filed early this year, DNCY accuses the NPS of breach of contract for not requiring Aramark to purchase all of their assets, of moving forward with the new concessioner contract without coming to an agreement on the value of the assets in question, and of attempting to devalue the trademarks by not taking DNCY up on their offer to allow for continued use of the historic names while litigation moves forward. This last, they say, was a ploy to create a public outcry to force DNCY to relinquish those assets for less than their fair value, ultimately to the financial benefit of the NPS and Aramark.

DNCY also says that the NPS, in its failure to negotiate and agree upon a fair value for what is termed “possessory interest” and “other property” before putting out a prospectus to attract bidders on the new contract, put DNCY in the position of submitting a bid based on errant information. Had they known that the NPS was not going to honor their contractual obligation to require any new concessioner to purchase those assets, DNCY says their bid would have been different, and they may have won the contract which was ultimately awarded to Aramark.

So let’s see how we got here.

Since 1899 the Curry Company, in various incarnations, had operated concessions in Yosemite National Park. In 1973, the Curry Company was purchased by MCA, Inc., which was later bought by Matsushita Electric Industrial Company of Japan in December 1990.

Public uproar over Japanese acquisition of American assets, along with pressure from then-Secretary of the Interior Manuel Lujan, Jr., resulted in an agreement to sell Yosemite Park & Curry Company (YP&CC) to the National Park Foundation (NPF) in early 1991, for a reported $49.5 million. The foundation then immediately turned over the 800 or so park buildings in which the Curry Company held an interest, along with their possessory interest, to the National Park Service. The NPS then went in search of a new concessioner to take over the operations within the park.

Enter Delaware North.

DNCY took over in Yosemite in 1993 by purchasing the stock of YP&CC as their contract was expiring, for $61.5 million. They also took on all their liabilities. That purchase, says DNCY in court documents, included their obligation to purchase “other property” and pay Curry Company “the fair value thereof.”

A quick definition of terms:

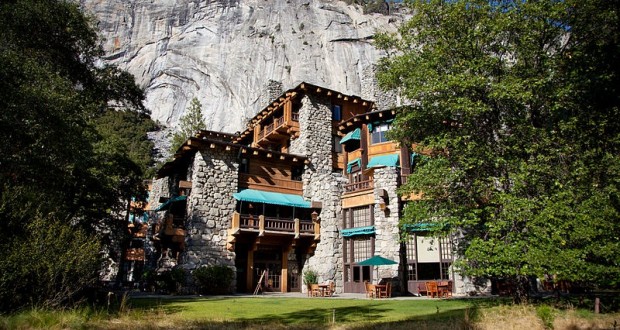

“Possessory interest” is the right to occupy and control a piece of property without establishing ownership. The structures in Yosemite belong to the U.S. Government. When the National Park Foundation took possession of all the structures in the Park, they acquired the possessory interest in those properties built by Curry Company, including The Ahwahnee, Yosemite Lodge and Curry Village.

“Other Property” includes everything else; much of the current dispute revolves around what is deemed “other property.”

- When DNCY bought YP&CC, they acquired that “other property,” including customer mailing lists, registered and common law trademarks, service marks, and logos that had already been registered by YP&CC or MCA, Inc. These acquisitions included Half Dome, Wawona, Badger Pass, Bracebridge Dinner, and The Ahwahnee Hotel name.

- Some trademarks held by DNCY are decades old and were in existence prior to the time the company became the concessioner. For example, they say, “The Ahwahnee” name was used by the Curry Company as far back as 1927. It was registered by the Curry Company in 1988, and purchased by DNCY in 1993 when they bought YP&CC.

- In quoting from the recently-expired contract between DNCY and the NPS, upon designation of a new concessioner, “DNCY will sell and transfer to the successor designated by the Secretary [of the Department of the Interior] its possessory interest in concessioner and government improvements, if any…”

- The contract further stated DNCY would sell and transfer “all other property of DNCY used or held for use in connection with such operations,” and that the Secretary “will require such successor, as a condition to the granting of a contract to operate, to purchase from DNCY such possessory interest, if any, and such other property, and to pay DNCY the fair value thereof.”

DNCY has no choice in the matter, they say. They are required under the terms of the contract to sell those trademarks and other assets used to operate in Yosemite, to Aramark, and cannot continue to use them. It’s not a matter of “these are mine, and you can’t have them,” but rather, “these are mine, I bought them from the guy before, and now you have to buy them from me.”

So there’s the sticking point: DNCY expected the NPS to require Aramark to purchase their “possessory interest” and “other property” as stated in the contract. They assert that they were operating from that belief, both in drafting their bid to retain the concessioner services contract in Yosemite, and in preparing for the change-over once Aramark was awarded the contract.

The NPS argues that this “other property” need not be purchased before the new contract goes into effect, and says it is “historically standard practice” to negotiate and close on that part of the deal after the change-over takes place.

However, argues DNCY, it’s impossible to negotiate a financial agreement when you haven’t agreed on the value of the elements of the deal. Though Aramark took over Park operations on Mar. 1, the value and scope of what DNCY owns has yet to be determined.

Any items of possessory interest would include major improvements to buildings or infrastructure, apart from regular maintenance. Other Property is listed as the company’s numerous operational assets, including intangible property such as trademarks, as well as internet domain names, mailing lists, photo inventories used in marketing, maintenance records for company and government owned assets, and numerous other assets.

As for the public uproar over the trademarks, DNCY states that their contract “does not limit in any way DNCY’s rights to own, maintain, create, use and register trademarks, service marks and logos related to its operations in Yosemite,” or to seek or obtain NPS’s consent or approval to do so.

As for the public uproar over the trademarks, DNCY states that their contract “does not limit in any way DNCY’s rights to own, maintain, create, use and register trademarks, service marks and logos related to its operations in Yosemite,” or to seek or obtain NPS’s consent or approval to do so.

The NPS argues that the concessioner’s business activities are strictly limited to those authorized by the contract, which does not authorize any trademark or service mark registrations. It does require the concessioners to have “full NPF approval” for any such activity, which the NPS says was never sought. However, they do admit they “had actual knowledge of plaintiff’s intermittent use of trademark registration symbols on certain printed materials.”

DNCY asserts that the value of the trademarks has grown during their tenure in the Park, as they are “associated with consistently high-quality hotel and resort experiences and services provided by DNCY,” adding that, “had DNCY not provided the quality services it did, the value of the trademarks would have suffered.” NPS responds that “much of the goodwill claimed by DNCY is attributable to the location of the Concession Facilities within the unique landscape of Yosemite National Park” and the “highly-regulated concession contract with NPS.”

DNCY states in their complaint that the appraised value of the intellectual property portfolio they’ve developed over the years is “no less than $44 million,” further asserting that the NPS has offered no documentation of its own to counter that figure, only saying they disagree with DNCY’s valuation.

“DNCY has also cultivated and significantly grown a customer database, which now contains 75 different informational fields for more than 720,000 customers. DNCY also developed a portfolio of Yosemite-related internet assets, including 17 domain names, websites, and multiple social media accounts.” The NPS says they lack sufficient information to affirm or deny that statement.

The NPS also disagrees with DNCY’s valuation of their “possessory interest,” stating that everything the company is claiming falls under contractual repair and maintenance, or rehabilitation work. DNCY values their non-routine capital improvements at $14.2 million, while NPS says not only was the company contractually obligated to perform that work, they never listed it in their Annual Financial Report (AFR) as capital improvements. NPS states that anything installed on a government building becomes the property of the United States, adding that DNCY did not seek a “possessory interest determination” prior to making any major improvements.

Nearly two years before DNCY’s contract with NPS was set to expire, the company contracted American Appraisal Associates, Inc. (AAA) to do an independent appraisal of their assets, and AAA arrived at a valuation of $98.6 million. DNCY notified the NPS of that approximate valuation on May 30, 2014. Three days later, the NPS requested additional information to support that number, and the two parties corresponded back and forth until July 3, 2014, when the NPS requested specific documentation as to all items of property related to the contract.

“Before DNCY could respond to this request, on July 9, 2014, the NPS issued the prospectus …for the new concession contract at Yosemite,” says the company in their complaint. The prospectus informed the potential offerors that under the contract the next concessioner must purchase DNCY’s “other property used or held for use in connection with the operation” and stated that this “includes personal property such as furniture, trade fixtures, equipment, and vehicles.”

The NPS prospectus estimated the value of DNCY’s Other Property at $22.5 million, but did not reveal to interested bidders of DNCY’s appraised value of $98.6 million. The company says it has had two separate appraisals, with similar results, and offered to make their documentation available and arrange for a meeting between AAA and the NPS, so they could go over just how they arrived at those figures. DNCY says the NPS never took them up on that offer.

DNCY also states that if the NPS disagreed with their valuation, they should have had their own independent appraisal done, but never did so.

At that point, DNCY says, the NPS adopted a strategy designed to minimize the amount Aramark would have to pay DNCY, including “devising and implementing a plan to change the iconic names of properties in Yosemite apparently in the mistaken belief that the name changes would drive down the value of DNCY’s trademarks in those names and create a public outcry that would force DNCY to relinquish the Other Property for less than its fair value, ultimately to the financial benefit of NPS and Aramark.”

On several occasions, DNCY offered to transfer the trademarks directly to NPS, “…so long as DNCY’s right to continue to seek fair value for its property is not diminished.” If the NPS was not willing to take ownership of the trademarks, DNCY has said they were willing to place the trademarks in escrow under the control of the NPS “until the respective rights and obligations of DNCY, NPS and Aramark are resolved through the Litigation or otherwise.” The NPS, they say, refused their offer.

On Jan. 26, the NPS filed a petition with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office asking that seven different trademarks issued to DNCY be cancelled and transferred to the NPS, stating that DNCY is relying on the trademark “to support its inflated demands for compensation” in its breach of contract suit against the United States, “causing damage and injury to the National Park Service by having to defend and unmeritorious suit.”

And so we find ourselves with tape over the plaques at the Ahwahnee Hotel, and staff trying their best to remember to call it “The Majestic Yosemite Hotel,” likely without much success or cooperation from visitors.

To read DNCY’s discussion of the trademark issue, click here.

To read the entire text of DNCY’s Amended Complaint filed on Jan. 25, 2016, click here.

To read the NPS’s petition to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, click here.

The NPS continues to demonstrate it’s poor stewardship of Federal lands, which is not surprising given the corruption in all government agencies. One contracts with the government at their own peril…it is sad to see this lovely area being torn by political correctness and greed.